Last year, an average of 9,500 tonnes of refined petroleum products was consumed daily by individual, residential and commercial consumers.

With national consumption ending 2017 at 3.46 million tonnes, it was not surprising that oil imports for the year firmed up to almost US$2 billion, representing 15.7 per cent of the value of the year’s total imports.

For an economy that is projected to enjoy annual growth rates of above five per cent in the medium-to-long term, more refined petroleum products will surely be needed to help fuel additional cars and ships, power industries and keep thermal plants running for existing and new factories to operate.

Although a good prospect, the projected strong demand for refined petroleum products begs the question how much of the resulting returns will return directly into the local economy? Better put, what will be the share of indigenous firms in meeting that demand?

At the heart of that question are the ownership structure and the market share of current bulk oil distribution companies (BDCs) and oil marketing companies (OMCs) – the firms that offtake, wholesale and retail the products to end consumers in the country.

Since time immemorial, a critical mass of Ghana’s promising economy has been resigned to foreign interest, with the telecommunication, mining and now petroleum subsectors virtually becoming the sole prerogative of majority foreign-owned firms.

While no local company currently operates in the multibillion dollar telecoms industry, the few ones in the extractive sector are at the periphery and best known for their support service roles.

The banking subsector is another victim. Of the 30 banks currently in operation, more than half – 17 banks – are majority foreign-owned. The minority domestically controlled banks are fragile – less capitalised and altogether control less than 40 per cent of the industry’s business.

Given that these are the blue-chip areas of the economy, locals being on the periphery marginalises the entire country.

In the downstream petroleum subsector, however, there is hope, thanks to the dominant role of the Ghana Oil Company Limited (GOIL).

As a market leader, its existence and sway is not just critical for the country but opportune for all the good reasons.

The inspiring journey

Despite a rocky start in the early 1990s, GOIL has fruitfully weathered its own version of corporate storms to now emerge an enviable company worthy of emulation by competitors and state-owned enterprises (SoEs).

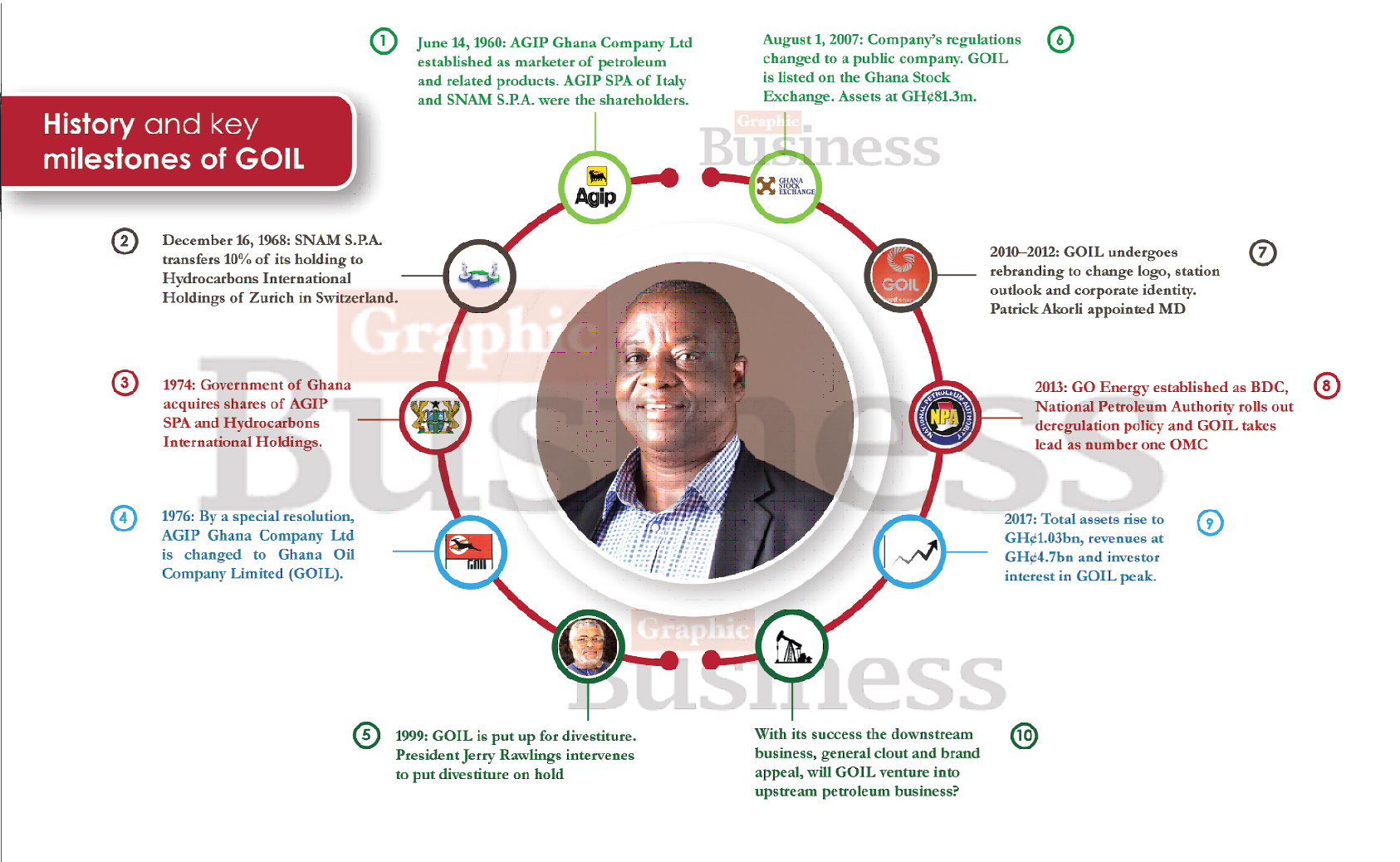

After a historic acquisition in 1974 which made the government a majority shareholder, the company has gone through various turbulent times, including surviving a divestiture scare in 2000 and subsequently listing on the Ghana Stock Exchange (GSE) in 2007, to now become the number one OMC in the country.

Although currently a household name, GOIL’s past was tortuous; the company was held down by limited reinvestment, rising debts and poor corporate governance practices.

The decision to list in 2007 was, therefore, opportune. It brought with it new energy, hope, good corporate governance and fresh funds for reinvestment.

As these positives took hold, the fruits started showing. GOIL’s total assets soon strengthened from GH¢81.3 million in 2007 to GH¢121 million in 2011. Market share also improved to around 11 per cent, placing GOIL on number three, behind Shell (now Vivo Energy) and Total.

Thanks to growth in market share and diversification, gross revenues resumed a growth trajectory, resulting in handsome profits and dividend payouts to shareholders.

From 2011 onwards, GOIL regained its momentum in a direct reversal of its pale self prior to the listing in 2007.

The leadership factor

Five years after going public, GOIL’s board and management decided to rebrand the company.

In the process, it successfully shook off its distressed and old self to usher in a new and exuberant oil marketer with new values, passion and a strong commitment to offer high customer service and value for shareholders. It also achieved ISO certification and ratification as a further endorsement of the quality of its products.

In 2012 too, the board appointed Mr Patrick A. K. Akorli as Managing Director (MD).

An astute accountant, Mr Akorli was elevated from his previous position of finance manager to MD to help lead the new phase of the company.

His previous association with the company meant that he was well aware of GOIL’s challenges and prospects.

“I had been the chief accountant, controller, treasurer, chief internal auditor and then finance manager,” he recounted in an interview.

In the years that followed, Mr Akorli and his team led GOIL’s transformation from a third- placed OMC to number one, expanded into the BDC business and endeared the brand to all consumers.

Credit to staff

Little by little, the board and the Mr Akorli-led management started revamping GOIL’s finances. As of 2014, the company’s revenue had strengthened to GH¢1.6 billion, assets were GH¢340.8 million and net profit had peaked at GH¢20 million.

Market share also almost doubled to 20 per cent for the oil marketing business and 21 per cent for the bulk oil distribution business, making the GOIL Group a leader on both sides.

Thanks to the consistent posting of profit, dividend payments became an annual affair and GOIL’s share price began to strengthen. This endeared the company and its MD to shareholders.

The result was a rejuvenated GOIL that gave competitors a run for their money.

On these positives, Mr Akorli insists they are the result of team work that speak volumes about the competence of GOIL’s human capital.

“I won’t say I brought anything new but because I was an internal person, I knew that we had technical expertise; one of the most competent workforce in the downstream industry,” he said.

Diversification

Around 2013, most BDCs were debt-ridden, forcing them to insist on cash from OMCs in return for products delivered. This affected GOIL, which was then the largest off-taker.

Mr Akorli recalled that management “realised that it was becoming difficult and the rebranding project in 2012 would be unsuccessful if we didn’t take time”.

GOIL’s response was strategic: Set up GO Energy as a BDC subsidiary.

Also, in July that year, deregulation took off, making it possible for market forces, not the National Petroleum Authority (NPA), to determine prices of refined petroleum products. It was the first of its kind in the country.

Driven by the fruition of the rebranding exercise and previous investments, the coming on board of GO Energy and some strategic decisions, GOIL moved from the third position to number one in terms of market share and brand appeal.

Since then, the company has not looked back.

Today, the health of its balance sheet and the strong growth in market share give credence to what foresight, focus and a clear sense of purpose can do for SoEs in the country.

Benefit to shareholders

The company’s enviable transformation over the years signals good times for shareholders. As growth surges on the back of a resilient management and costs remain under control, increased revenues will lead to strong profit.

This should translate into additional value to shareholders in the form of share price appreciation and annual dividend payouts.

In fact, since going public in 2007, GOIL has maintained an enviable record of year-in, year-out dividend payouts.

Except 2016, when dampened revenues on the back of subdued sales caused the company to maintain its 2015 dividend of GH¢0.25 per share, the company has habitually grown its annual dividend from GH¢0.0085 per share to GH¢0.028 per share in the 2017 financial year. This makes it one of the few listed companies with a consistent dividend payment culture.

Earnings per share has equally strengthened; it rose from GH¢0.019 in 2007 to GH¢0.166 last year. This means that the company’s profitability has more than quadrupled twice within the two decades.

Looking ahead

Now, it is evident that GOIL is rubbing shoulders with the big names in the subsector.

But unlike competitors, the group has a stronger balance sheet on which to fall on for any future big-ticket transactions.

As of December last year, its total assets had risen to GH¢1.03 billion, funded largely by a 140 per cent growth in stocks from GH¢47 million in 2016 to GH¢114 million in 2017. Liabilities were kept under control at GH¢669.4 million within the period. Revenues, which were GH¢4.1 billion in 2016, also grew by 43 per cent to GH¢4.7 billion in December 2017.

Net profit remained strong at GH¢65.1 million, up by 22 per cent from GH¢53.4 million in 2016.

With this and a competent workforce, the company can continue to serve as an opportune stabiliser in a volatile and deregulated downstream petroleum business.

Together with strategic investments in the Takoradi Port, the proposed Bitumen Plant and the three LPG gas plants, GOIL is cementing its role in the subsector for future prospects. And with the strong balance sheet, the company is empowered to continue to diversify into adjoining areas to help maintain growth in top and bottom line.

GOIL’s growth can, however, be hampered by its weak cashflows. This originates, largely, from delay in payment for supplies to strategic national institutions, including the security services.

As a result, the company has had to rely heavily on overdraft facilities, which come at throat-cutting interest rates.

Given that it feeds interest expense, which also weakens profitability, there is the need for an innovative approach to help improve the group’s liquidity position.

This aside, GOIL’s success over the years speak volumes of what a competent board, hardworking and visionary management and innovative staff can do.

GOIL’s meteoric rise to the top should be celebrated for three key reasons: A strong GOIL is a testament of the Ghanaian ingenuity; it discourages collusion and price taking by consumers in the petroleum downstream business and also retains capital as a cure to all the challenges associated with capital flight.

However, one key question that time and corporate vision will answer is whether or not GOIL will venture into the upstream petroleum business.

Its strong balance sheet, enchanting brand and desire to diversify places the company on a strong pedestal to be able to make a proper entry and meaningful impact in an area that is virtually resigned to multinationals.