There are nearly 200 countries in the world today, all competing for resources, trade and attention. So if you're a nation in a remote corner of the planet, how do you go about telling everyone that you exist?

Countries are increasingly copying the marketing tactics that companies use to raise their profiles, and let people know that they are open for business. Welcome to the world of nation branding.

A strong country brand should encourage tourists, trading partners and investors all at once. But having a snazzy logo, and an advertising budget won't sell a product that people don't want.

So what should a country do to try to boost its profile? The South American country Chile is a good case study.

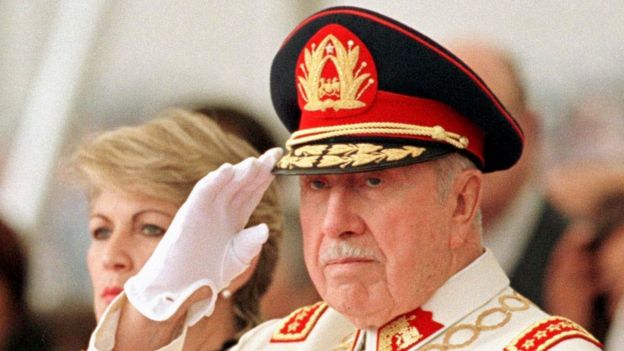

The military dictator Augusto Pinochet ruled Chile from 1974 to 1990

In the 1990s, after the brutal regime of Augusto Pinochet had come to an end, Chile set out to burnish its image on the world stage.

"Chile's image used to be much more vague," says Jorge Cortes, digital marketing manager at Fundacion Imagen de Chile, the organisation which has, since 2009, guided Chile's brand-building programme.

"In fact, perception studies have shown that we were spontaneously associated with certain aspects that do not define us, such as coffee and carnival."

In other words, many of the people they surveyed didn't think that Chile was any different from Brazil. Yet without Brazil's enduring calling cards - yellow football shirts, samba, Rio de Janeiro and its famous carnival, the Amazon rainforest - what could Chile do to make itself better known?

While Chile does have its own carnivals, they aren't as big or as prominent as those in Brazil

Some of the early attempts to stand out were a little bizarre. The country dragged a giant iceberg halfway around the world to exhibit at the World's Fair in Seville in 1992. It certainly attracted attention, though not all of it positive.

Then in 2005, it ran a campaign based around the slogan "Chile: All Ways Surprising".

Chile doesn't do slogans any more. It now takes a subtler approach, focusing on stability, the country's geographic diversity - which ranges from deserts to glaciers - and the "entrepreneurial character of the people".

These it sells in public relations campaigns, and via social media, events, and an outreach programme targeting 380 companies across Chile, to get them all singing the same song.

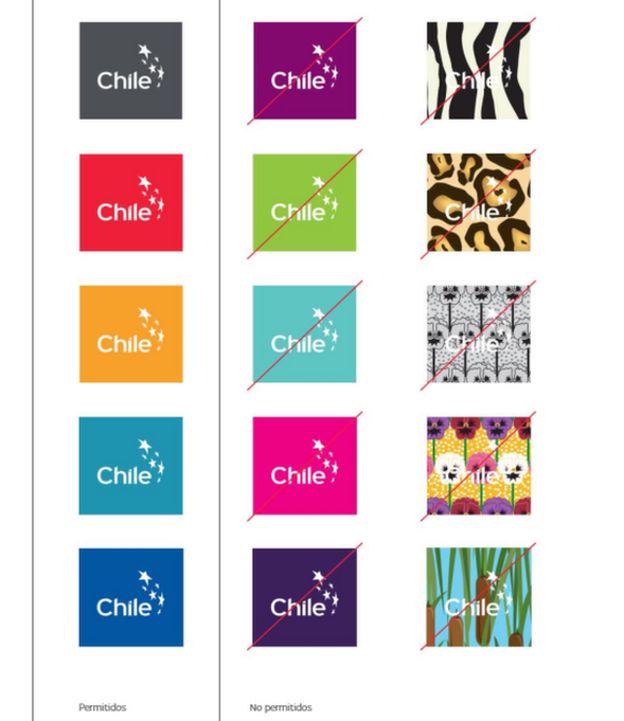

There are very specific rules about which logos, typefaces, and even photography you can use. There are five specific brand colours - exact shades of grey, red, yellow and two blues.

It's the kind of brand discipline of which any Fortune 500 company would be proud.

Permitted and non-permitted colours of the Chile brand logo

Chile's marketers claim that international audiences, particularly the kind of people who might make investment decisions, now have a better impression of the country, from the attractiveness of the countryside to the stability of its government.

Mr Cortes cites two things that have helped to improve Chile's image - having a long-term strategy, and getting citizens on board.

"It is essential to strengthen Brand Chile inside the country in order to effectively promote it abroad," he says.

"Each Chilean is responsible for this great task, and is called to become an ambassador of the country's unique and positive qualities."

Echinopsis cacti in the Chilean desert. Chile is a rare example of a nation that has improved its image worldwide

But have efforts to boost Chile's profile actually worked? These things are very hard to quantify, but overseas investment into the country has certainly risen strongly over the past decade or so.

Foreign direct investment into Chile increased from $4.3bn (£3.3bn) in 2003 to $30bn in 2012, according to the Central Bank of Chile. Meanwhile, visitor numbers to the country hit a record high of 6.45 million people last year.

So should other countries looking to promote themselves follow Chile's lead?

Simon Anholt, one of the leading figures in the world of nation branding, says that Chile is a very rare example of a country that has been able to improve its global image.

However, he wonders if this has been through marketing at all.

Instead, perhaps Chile's profile has improved simply because it has gone from a military dictatorship to a successful and open democracy with a growing economy that is increasingly open to the world.

Simon Anholt helped to invent the concept of nation branding, but he is now sceptical about whether it has any benefit

Mr Anholt, a former advertising executive, is now in fact highly sceptical that nation branding is even something that works.

Since 2005 he has compiled a vast international survey of public perceptions of nations, the Anholt-GfK Nation Brands Index, which now amounts to 430 billion data points.

"I have been looking for 20 years for a single properly documented case study of one single country, city or region that has demonstrably moved the needle, even by the most microscopic degree, on its global image as a result of marketing, messaging or communications. And I'm still looking," says Mr Anholt.

He believes that only one other country has been able to improve its global image in recent years, and again not through marketing - South Korea.

For South Korea the hit single Gangnam Style and other Korean pop music, or K-pop, songs may be a factor in boosting its image. And also the growing popularity of Korean restaurants around the world.

Mr Anholt also believes it's down to South Korea's increasing efforts to engage with North Korea.

"South Korea has been playing a more principled, more prominent role in world affairs," he says.

"It's doing more about North Korea than it used to. People are less confused about which is the good Korea and which is the bad one."

Psy performs his hit Gangnam Style. Could the rise of K-pop be a factor in South Korea's growing international reputation?

While South Korea and Chile are success stories, Mr Anholt cautions that it is possible to damage your national brand.

The football World Cups in South Africa and Brazil produced - to many people's surprise - not an improvement but a dent in those countries' reputations.

The world's media descended on the two nations, and before a ball was even kicked they generated hours and hours of negative coverage of poverty and social problems, which some international audiences may not have been previously aware of.

Ultimately, Mr Anholt believes that the best way to improve a country's image is for it to contribute to the well-being of the world beyond its borders rather than spending money on advertising.

"If you really want to earn a better reputation, the best thing you can do is stop chasing after it," he says.

"There is something very unedifying about the spectacle of a country or indeed a person saying, 'Do I look good in this?' and fussing about its image. It just makes you look like a sad loser."