Labour has promised to give every home and business in the UK free full-fibre broadband by 2030 if it wins the general election.

The plan would see millions more properties given access to a full-fibre connection, though Prime Minister Boris Johnson said it was "a crackpot scheme".

If the plan went ahead and was completed on time, would it still be useful in 2030?

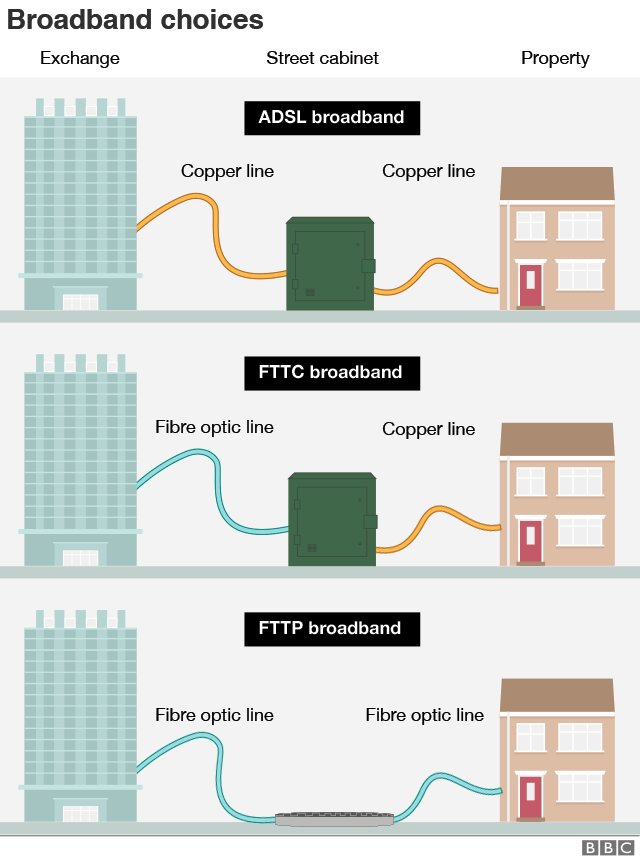

There are three main types of broadband connection that link the local telephone exchange to your home or office:

The old landline telephone infrastructure across the UK used copper cables, but accessing the internet over copper cables is slower than over fibre optic cables.

Fibre optic cables are made from glass or plastic and use pulses of light to transmit data, offering much faster internet access.

Full-fibre broadband refers to an FTTP connection: the entire line from the telephone exchange to your home uses fibre optic cables.

Currently, the UK government defines superfast broadband as having speeds greater than 30 megabits per second (Mbps). A megabit is the standard measurement of internet speed.

Ultrafast is defined as a speed greater than 100Mbps.

A connection using both fibre and copper (FTTC) can reach speeds of about 66Mbps.

But a full-fibre connection (FTTP) - with no copper - can offer much faster average speeds of one gigabit per second (Gbps) - that's 1,000Mbps.

Full-fibre can also deliver very low latency: that means less delay between sending a request and getting a response.

That is not just important for video gamers. Low latency connections promise new opportunities for remote work, especially in fast-paced industries that cannot afford delays.

There are other types of very fast connection as well. Virgin Media uses a different type of cable for the last section that comes into your house, which in theory can offer speeds of up to 10Gbps.

There is also a service called G.fast, which uses a special pod to boost the speed of the standard copper cable connection.

Predicting what the future holds for technology is obviously difficult.

But full-fibre broadband, where ultra-fast optical cables carry data right into your home or office, is currently the "gold standard".

"There is no doubt that we need fibre connectivity, in particular all the way to the home. That's something everybody is on board with across the industry and political parties," said Matthew Howett, an analyst at Assembly Research.

While full-fibre connections can currently promise speeds of one gigabit per second, future upgrades could potentially offer speeds in terabits per second. (One terabit equals 1,000 gigabits.)

That could be made possible by replacing the equipment at either end of the cables - in the telephone exchange and at home - without laying new cables.

If, come 2030, there is a new emerging technology and countries are thinking about replacing their full-fibre systems, the UK would start on the same footing.

Wireless connections can be a useful way to connect remote homes to the internet, but 5G may not be the answer for sparsely populated areas.

5G networks can operate on several different frequencies, but the higher frequencies do not penetrate buildings and trees as well as the lower frequencies.

Using those high frequencies requires many more transmitters, closer to the homes and offices that need internet access.

And those so-called nano-masts are typically connected to the internet backbone by fibre.

"Investing in fibre improves both fixed line services and helps to support connecting the many new nano-masts needed for 5G at its highest speeds," said Andrew Ferguson from the news site Thinkbroadband.com.

High-frequency 5G will require more transmitters

However, the government plans to auction lower-frequency spectrum - freed up from the digital TV switchover - for 5G services.

"The 700MHz frequency band that will be auctioned is good at covering large rural areas," said Mr Howett.

"Anything freed up from that switchover from analogue to digital TV means you can reach more people with fewer base stations."

However, even if the UK focused on national 5G coverage, guaranteeing a stable connection to every home would be difficult.

Atmospheric conditions can lead to variation in latency with wireless connections.

"The problem with the final leg still being wireless is easily illustrated by the problems people have with existing wi-fi," said Mr Ferguson.

"People often find they cannot cover their whole home without additional wireless repeaters.

"And in the worst case scenario, a double decker bus could park between you and the lamp post across the street.

"Full-fibre into the building technically gives a much better experience and avoids the variables that 5G cannot always overcome."