France's president and his counterparts from the Sahel region are due to meet to discuss military operations against Islamist militants in West Africa. We look at the figures behind the conflict, which is slipping out of control.

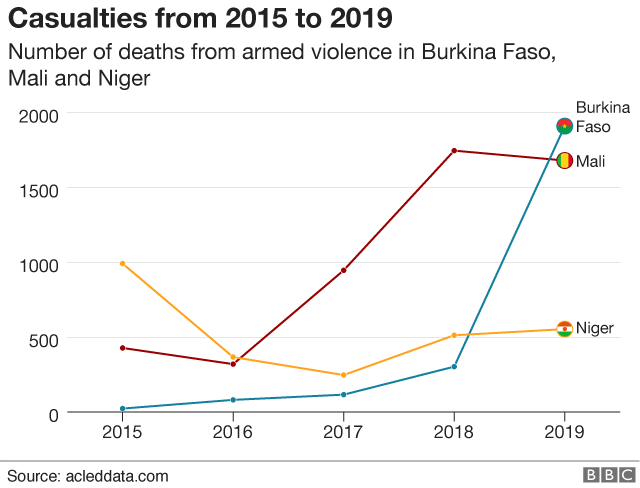

Attacks on army positions and civilians across the region are occurring with increasing regularity, despite the presence of thousands of troops from both the countries affected and France. Last year saw the highest annual death toll due to armed conflict in the region since 2012.

Last week, 89 soldiers from Niger were killed in the latest attack to see dozens of deaths among regional armed forces. France has also suffered significant casualties, losing 13 soldiers in a helicopter crash in Mali in November.

The Sahel region, a semi-arid stretch of land just south of the Sahara Desert, has been a frontline in the war against Islamist militancy for almost a decade.

However, it is increasingly clear that the problem facing Chad, Niger, Mali, Burkina Faso and Mauritania (known as the G5 Sahel) is not just the presence of armed groups, and that more than military action is urgently needed to address a worsening humanitarian crisis, climate change and development challenges.

The overarching worry is that the crisis could spread further across West Africa.

The security crisis in the region started in 2012 when an alliance of separatist and Islamist militants took over northern Mali, triggering a French military intervention to oust them as they advanced towards the capital, Bamako.

A peace deal was signed in 2015 but was never completely implemented and new armed groups have since emerged and expanded to central Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger.

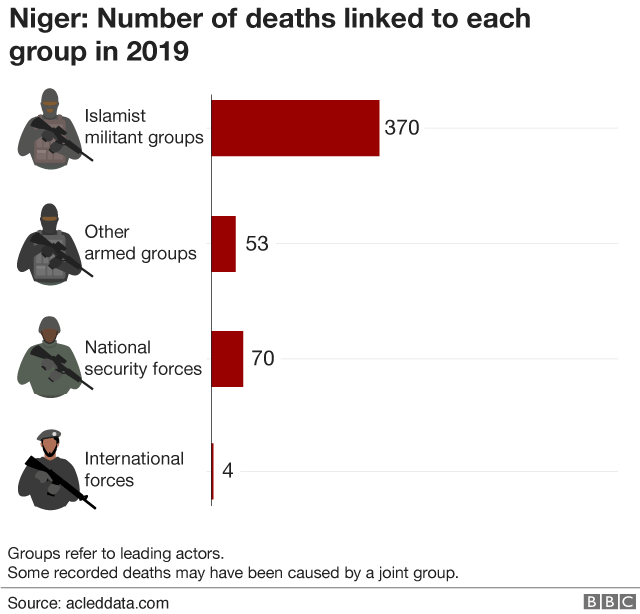

Casualties from attacks in those countries are believed to have increased fivefold since 2016, with over 4,000 deaths reported last year alone.

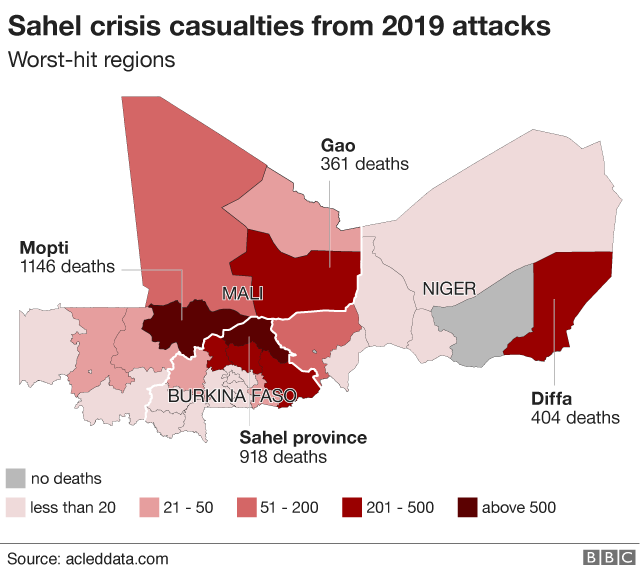

A stretch of land covering the border areas of Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger is at the centre of the insurgency and counter-terrorism operations.

Armed groups, including some linked to al-Qaeda and others the Islamic State group, have expanding their presence and capabilities.

The reasons behind their expansion are multiple:

In addition to the joint G5 Sahel countries, which have an estimated 5,000-strong force battling the militants, the French have had 4,500 soldiers deployed in the Sahel since 2013.

The UN also has over 12,000 peacekeepers in Mali, while the US has two drone bases in Niger, providing intelligence and training support throughout the region.

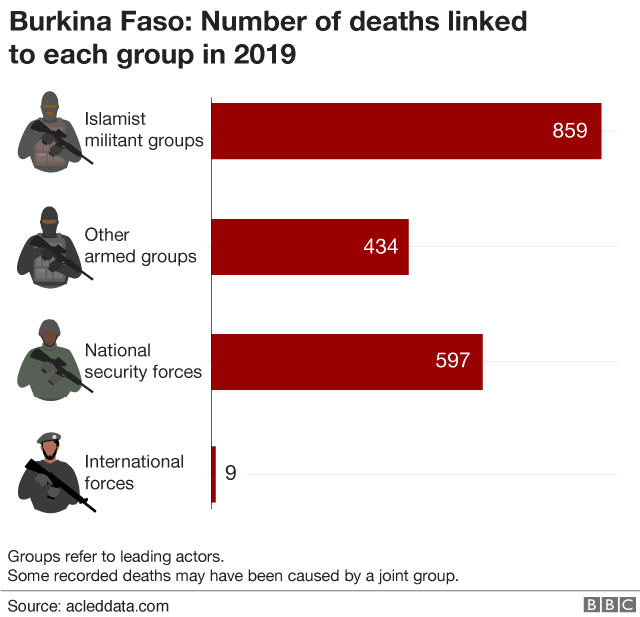

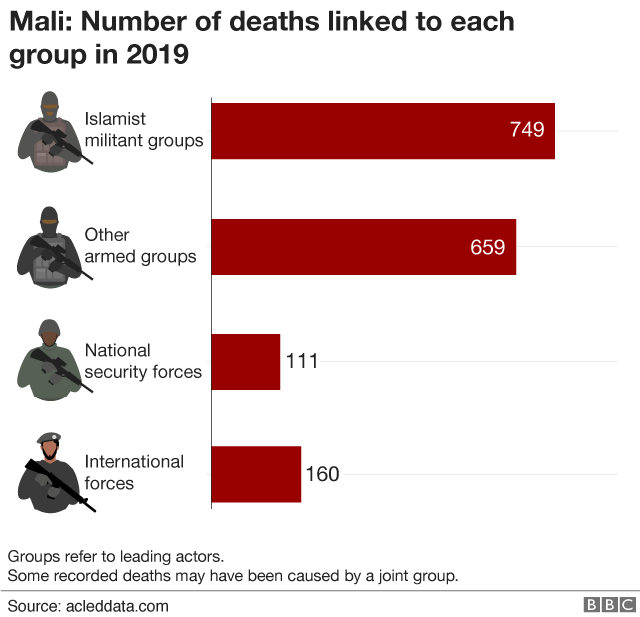

Amid the rising insecurity, so-called self-defence groups have been formed. In Mali and Burkina Faso, these militias are believed to be behind a number of massacres.

Most attacks on civilians remain unclaimed but the main armed Islamist militant groups in the Sahel are:

Ethnic tensions and economic rivalries have become mixed up with the Islamist insurgency, with accusations that members of the mainly Muslim Fulani ethnic group are linked to Islamists, which their representatives deny.

In addition, expanding deserts and climate change have magnified long-standing conflicts between mainly Fulani herders and pastoralists.

All this has led to the creation of ethnic militias on both sides, which have also been responsible for a horrific cycle of tit-for-tat mass killings.

Some security forces have been accused by human rights groups of unlawful killings during counter-terrorism operations.

Last week, a coalition of NGOs said that the "military response in the Sahel is part of the problem".

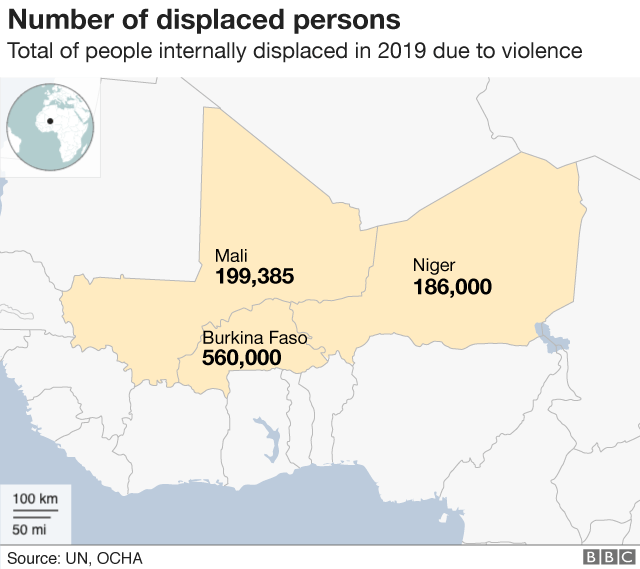

Action Against Hunger, the Norwegian Refugee Council and Oxfam estimated that the army operation in Mali had forced more than 80,000 people to flee their homes - about 40% of all those displaced in the country.

More about the crisis in the Sahel:

As the population in the region is set to double over the next 20 years, the violence is exacerbating development challenges.

Growing enough food for everyone will become increasingly difficult and this is not being helped by the numbers of people who have been forced to flee their homes.

In Burkina Faso, the number of people internally displaced has risen from 40,000 at the end of 2018 to more than 500,000 at the end of 2019 - that is more that 2% of the population. In Mali, the number has practically doubled.

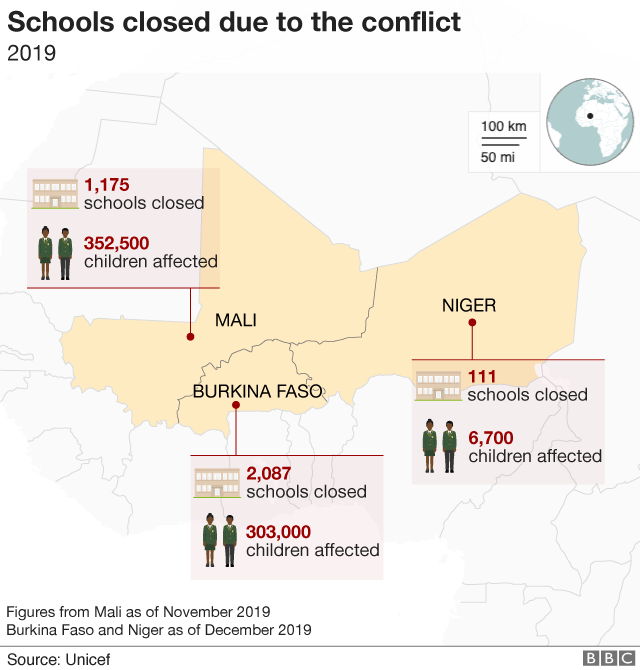

The violence is also storing up problems for future generations as some of the Islamist groups deliberately target schools and teachers, leaving hundreds of thousands of children without access to education.

They then become even more vulnerable to sexual exploitation, forced labour or recruitment into armed groups.