Doctors' use of Caesarean section to deliver babies has nearly doubled in 15 years to reach "alarming" proportions in some countries, a study says.

Rates surged from about 16 million births (12%) in 2000 to an estimated 29.7 million (21%) in 2015, the report in the medical journal The Lancet said.

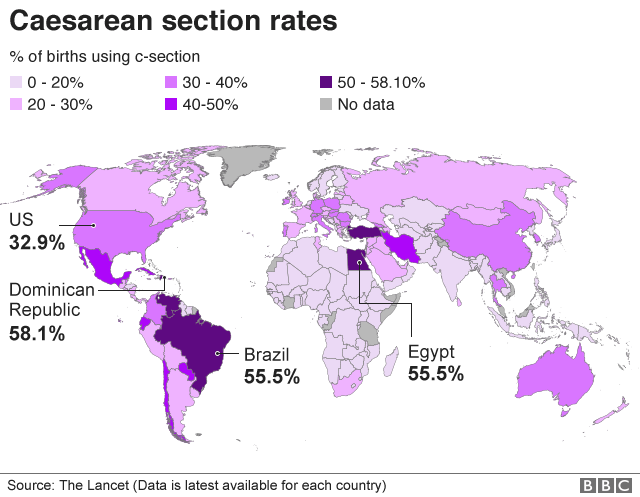

The nation with the highest rate for using the surgery to assist childbirth is the Dominican Republic with 58.1%.

Doctors say in many cases the use of the medical procedure is unjustified.

Until recently, the World Health Organization (WHO) suggested that Caesarean section - or C-section - rates of more than 15% were excessive.

The study analysed data from 169 countries using statistics from 2015 - the most recent year for which the information is available.

It says there is an over-reliance on Caesarean section procedures - when surgery is used to help with a difficult birth - in more than half of the world's nations.

Researchers reported a rate of more than 50% in the Dominican Republic, Brazil, Egypt and Turkey, though Brazil implemented a policy in 2015 to reduce the number of Caesarean sections performed by doctors.

They also found huge disparities in the use of the technique between rich and poor nations. In some circumstances, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, the surgery is unavailable when it is genuinely required.

Use in 2015 was up to 10 times more frequent in the Latin America and Caribbean region, at 44% of births, than in the west and central Africa region, where it was used in just 4% of cases.

The study urges healthcare professionals, women and their families to only choose a Caesarean when it is needed for medical reasons - and for more education and training to be offered to dispel some of the concerns surrounding childbirth.

A Caesarean section can be a life-saving procedure for both mother and infant if, for example, a baby is in an awkward position in the womb or if labour is not progressing as it should be.

Jane Sandall, professor of social science and women's health at King's College London and an author of one of the studies, told the BBC that the risk for mothers and babies can be both short and long-term.

"In particular, C-sections have a more complicated recovery for the mother, and lead to scarring of the womb, which is associated with bleeding, abnormal development of the placenta, ectopic pregnancy, stillbirth and preterm birth in subsequent pregnancies."

Prof Sandall says it is important to note that these are small but serious risks, but each of these risks increases with each time a woman undergoes the surgery.

"There is emerging evidence that babies born via C-section have different hormonal, physical, bacterial and medical exposures during birth, which can subtly alter their health. While the long-term risks of this are not well-researched, the short-term effects include changes in immune development which can increase the risk of allergies and asthma and alter the bacteria in the gut."

"There is the risk that comes with any type of surgery," Prof Sandall said, adding that multiple Caesarean procedures lead to a higher risk of maternal mortality when compared with a natural birth.

Earlier this week, the WHO published guidance highlighting the need to reduce unnecessary procedures that "cannot be medically justified".

"It is crucial that women who need Caesarean sections are able to access this potentially life-saving procedure," the WHO advises, adding that it is equally important that unnecessary procedures be avoided "so women and their babies are not put at risk".

Prof Sandall says that reasons vary from country to country and that with poorer nations, choices are extremely limited.

"Globally, drivers for the increasing rates vary between countries and include a lack of midwives to prevent and detect problems, loss of medical skills to confidently and competently attend a [potentially difficult] vaginal delivery, as well as medico-legal issues."

She adds that financial incentives exist for both doctor and hospital with the certainty of planned day-time deliveries, especially in private practices.

"In some cases the trend is system-driven. In Brazil, for example, the free public healthcare system is of poorer quality and pregnant mothers who can't afford private healthcare might be offered the procedure to help clear patients more quickly through the system."

"In China, a shortage of midwives can result in a lack of screening, meaning not only that necessary medical checks are not being carried out, but that there is a lack of expert help with assisting childbirth."

Variation exists within countries between the urban wealthy giving birth in private facilities where there are high rates of Caesarean section and the rural poor without access to the procedure, Prof Sandall says.

"The issue for women is how do you plan?" Prof Sandall says.

"Conjecture that blames mothers for the high Caesarean section rate, either because of their poor health - eg, obesity, hypertension - or because they are demanding medically unnecessary Caesarean sections due to fear or disinterest in labour ignores the wider systems issues that drive the growing reliance on caesarean sections.

"Pregnant mothers must have access to professional and informed advice in order to make a decision."

She adds that the focus must now be on providing more frontline staff at facilities in countries where the issue is of greatest concern.

"We need to start working with insurance companies in these countries to help with the provision of services and staff, as well as dealing with local and national governments to invest in healthcare."

A Caesarean section is when a baby is delivered by making a surgical cut in the abdomen and womb.

They fall into three categories:

Recovering from Caesarean surgery usually takes longer than from a natural birth and can result in some discomfort in the days following the procedure. The wound eventually forms a scar.