UK health chiefs are being urged to safeguard people's privacy as they develop an app to help tackle the coronavirus pandemic.

An open letter published by a group of "responsible technologists" warns that if corners are cut, the public's trust in the NHS will be undermined.

And it urges those in charge to be more open about their data-collection plans.

The BBC asked both NHSX - the health service's tech leadership unit - and the Department of Health to respond.

South Korea, Singapore and Israel are among countries that have already deployed apps that can help the authorities track who users have come into contact with, to help model the spread of the virus.

Taiwan has also introduced what it calls an "electronic fence" system that alerts the local police if a quarantined user leaves their home or switches off their handset for too long.

And in Europe, a number of mobile network operators have offered to provide anonymised data about users' movements to help identify potential "hot zones" where the virus might be at most risk of spreading.

The Prime Minister's advisor Dominic Cummings hosted a meeting at Downing Street on 11 March at which dozens of tech industry leaders were asked how they could help develop an app to tackle Covid-19 in the UK. But there has been no formal announcement about what it will do or when it will launch.

"It is not yet clear how data will be collected or used... nor what technical safeguards will be used," says the open letter.

"We are also concerned that data collected to fight coronavirus could be stored indefinitely or for a disproportionate amount of time, or will be used for unrelated purposes.

"These are testing times, but they do not call for untested new technologies."

The letter makes calls on Health Secretary Matt Hancock and NHSX's leaders to make three commitments, asking them to:

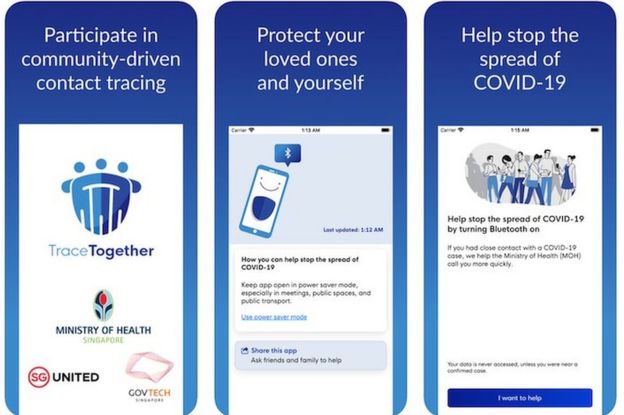

The letter highlights Singapore's TraceTogether app as an example of good practice.

It uses Bluetooth to identify when users are within 2m (6.6ft) of another person for more than 30 minutes.

The information is stored in an encrypted form on each person's phone, and Singapore's Ministry of Health must get their consent to upload it for contact-tracing.

In addition, the government says third-parties are unable to use the information to identify individuals.

When the app launched last week, it was accompanied by a plain-language and brief privacy FAQ.

Image copyright Singapore government

Singapore's TraceTogether app was released on 18 March

The letter's authors also warn that becoming over-reliant on smartphone surveillance tech could backfire, since many older and younger users do not own handsets that can install apps. In addition, they warn that current cellphone technologies are not good enough to distinguish between people in the same flat and those living in surrounding residences.

"This is not a time to innovate in haste and repent at leisure," lead author Rachel Coldicutt told the BBC.

"At a time when people both in and out of the NHS are under stress, it's important that any solutions driven by digital technologies are easy to understand and, most importantly, useful."

The data scientists and privacy campaigners behind this letter have seen what has happened in other countries fighting the virus - and they don't like it.

South Korea's self-quarantine app allowed users to communicate with health workers but also used GPS to monitor them, making sure they did not leave home. In China a range of apps use personal health information to alert people that they may have come into contact with someone who has been infected.

The argument is that we are in danger of allowing our huge concern in the short-term about stopping the spread of the virus to blind us to the long-term danger of ushering in a surveillance state.

But this may be a hard argument to sell to the public.

Right now, there is pressure on the government to do more, not less, and pressure on technology firms to lend their vast resources to what amounts to a war effort. And just as in wartime, people may be willing to accept the erosion of all sorts of freedoms they previously considered essential in pursuit of victory against the virus.

Having accepted that they can no longer go to the pub, many may now think submitting to some temporary tracking via their mobile phones is a smaller price to pay.

The key word, of course, is temporary.

The writer Yuval Noah Harari, who is quoted in the open letter by the data campaigners, warns that such measures have a nasty habit of becoming permanent. But he also says this: "When people are given a choice between privacy and health, they will usually choose health."