Two years ago today, a powerful ransomware began spreading across the world.

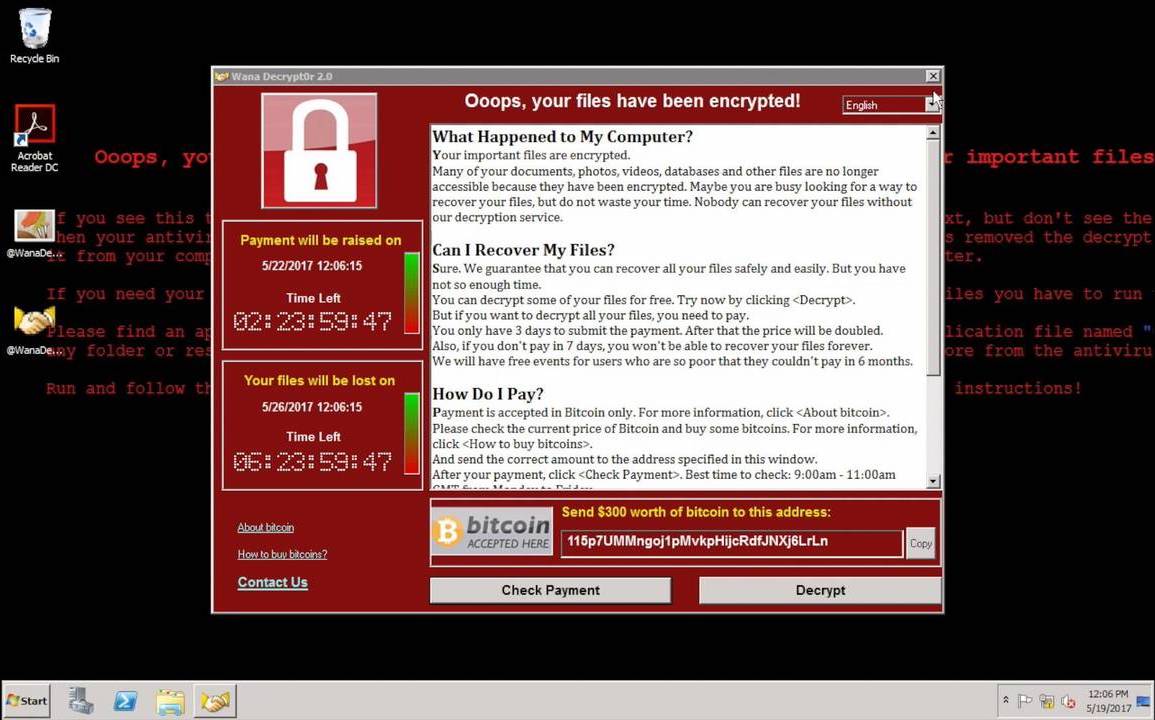

WannaCry spread like wildfire, encrypting hundreds of thousands of computers in over 150 countries in a matter of hours. It was the first time that ransomware, a malware that encrypts a user’s files and demands cryptocurrency in ransom to unlock them, had spread across the world in what looked like a coordinated cyberattack.

Hospitals across the U.K. declared a “major incident” after they were knocked offline by the malware. Government systems, railway networks and private companies were also hit.

Security researchers quickly realized the malware was spreading like a computer worm, across computers and over the network, using the Windows SMB protocol. Suspicion soon fell on a batch of highly classified hacking tools developed by the National Security Agency, which weeks earlier had been stolen and published online for anyone to use.

“It’s real,” said Kevin Beaumont, a U.K.-based security researcher at the time. “The shit is going to hit the fan big style.”

WannaCry relied on stolen NSA-developed exploits, DoublePulsar and EternalBlue, to hack into Windows PCs and spread through the network. (Image: file photo)

An unknown hacker group — later believed to be working for North Korea — had taken those published NSA cyberweapons and launched their attack — likely not realizing how far the spread would go. The hackers used the NSA’s backdoor, DoublePulsar, to create a persistent backdoor that was used to deliver the WannaCry ransomware. Using the EternalBlue exploit, the ransomware spread to every other unpatched computer on the network.

A single vulnerable and internet-exposed system was enough to wreak havoc.

Microsoft, already aware of the theft of hacking tools targeting its operating systems, had released patches. But consumers and companies alike moved slowly to patch their systems.

In just a few hours, the ransomware had caused billions of dollars in damages. Bitcoin wallets associated with the ransomware were filling up by victims to get their files back — more often than not in vain.

Marcus Hutchins, a malware reverse engineer and security researcher, was on vacation when the attack hit. “I picked a hell of a fucking week to take off work,” he tweeted. Cutting his vacation short, he got to his computer. Using data from his malware tracking system, he found what became WannaCry’s kill switch — a domain name embedded in the code, which, when he registered, immediately saw the number of infections grind to a halt. Hutchins, who pleaded guilty to unrelated computer crimes last month, was hailed a hero for stemming the spread of the attack. Many have called for leniency if not a full presidential pardon for his efforts.

Trust in the intelligence services collapsed overnight. Lawmakers demanded to know how the NSA planned to mop up the hurricane of damage it had caused. It also kicked off a heated debate about how the government hoards vulnerabilities to use as offensive weapons to conduct surveillance or espionage — or when it should disclose bugs to vendors in order to get them fixed.

A month later, the world braced itself for a second round of cyberattacks in what felt like would soon become the norm.

NotPetya, another ransomware which researchers also found a kill switch for, used the same DoublePulsar and EternalBlue exploits to ravish shipping giants, supermarkets and advertising agencies, which were left reeling from the attacks.

Two years on, the threat posed by the leaked NSA tools remains a concern.

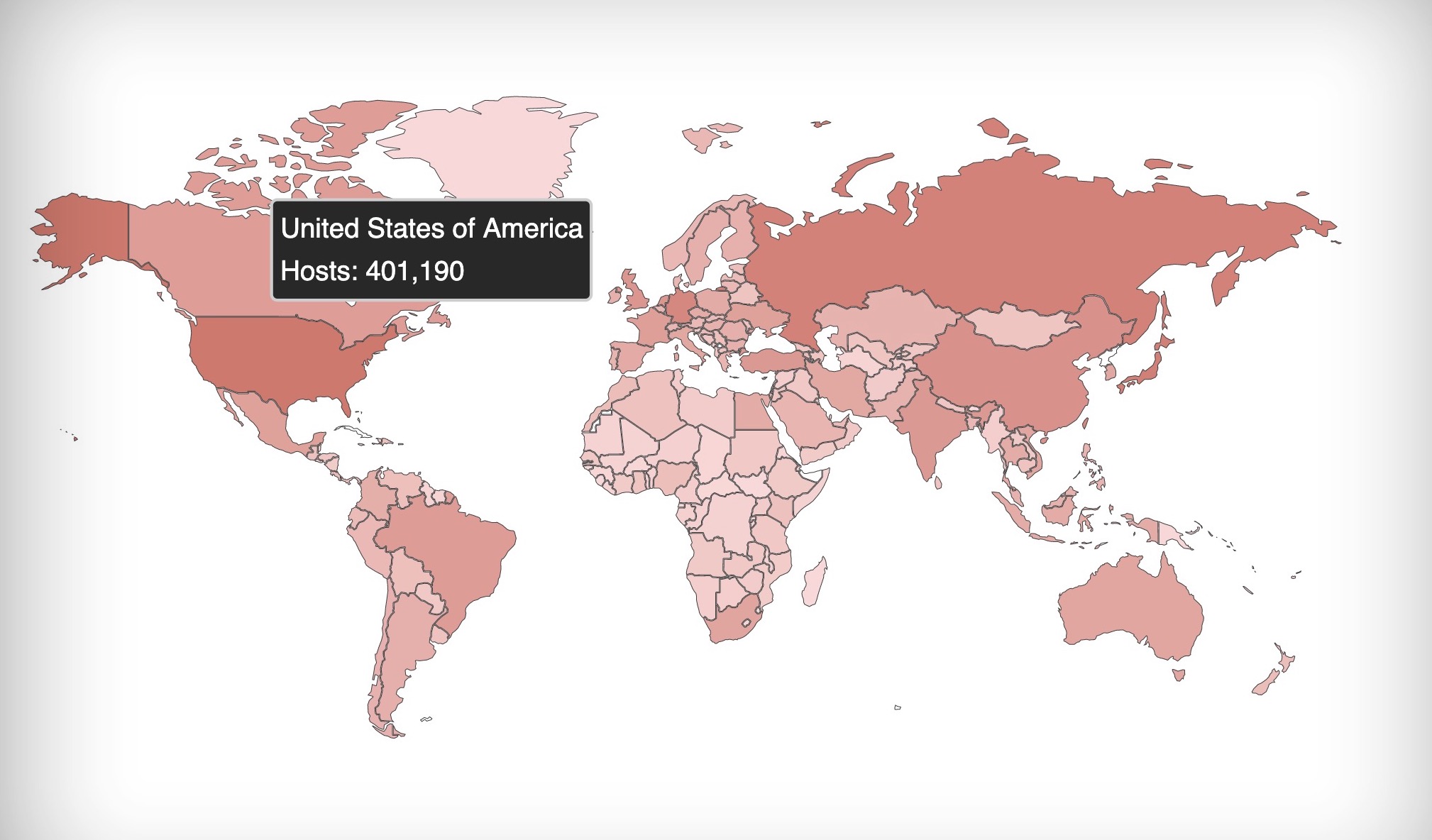

As many as 1.7 million internet-connected endpoints are still vulnerable to the exploits, according to the latest data. Data generated by Shodan, a search engine for exposed databases and devices, puts the figure at the million mark — with most of the vulnerable devices in the U.S. But that only accounts for devices directly connected to the internet and not the potentially millions more devices connected to those infected servers. The number of vulnerable devices is likely significantly higher.

More than 400,000 exposed systems in the U.S. alone can be exploited using NSA’s stolen hacking tools. (Image: Shodan)

WannaCry continues to spread and occasionally still infects its targets. Beaumont said in a tweet Sunday that the ransomware remains largely neutered, unable to unpack and begin encrypting data, for reasons that remain a mystery.

But the exposed NSA tools, which remain at large and able to infect vulnerable computers, continue to be used to deliver all sorts of malware — and new victims continue to appear.

Just weeks before the city of Atlanta was hit by ransomware, cybersecurity expert Jake Williams found its networks had been infected by the NSA tools. More recently, the NSA tools have been repurposed to infect networks with cryptocurrency mining code to generate money from the vast pools of processing power. Others have used the exploits to covertly ensnare thousands of computers to harness their bandwidth to launch distributed denial-of-service attacks by pummeling other systems with massive amounts of internet traffic.

WannaCry caused panic. Systems were down, data was lost, and money had to be spent. It was a wakeup call that society needed to do better at basic cybersecurity.

But with a million-plus unpatched devices still at risk, there remains ample opportunity for further abuse. What we may not have forgotten two years on, clearly more can be done to learn from the failings of the past.