A record-breaking goalscorer for club and country, an innovative coach who worked on three continents, a theatre co-star of Charlie Chaplin and an escapee from Germany during World War One. Fred Spiksley may well be the most interesting footballer you've never heard of.

A football superstar before the sport was familiar with the notion, the winger practised the beautiful game on the pitch and promoted its message off it.

He was also a flawed character - a compulsive gambler and womaniser who aspired to ride horses as a child but settled for betting away his money on them as an adult.

Born in Gainsborough in Lincolnshire in 1870, the boilermaker's son would travel to Europe, to the United States, Peru and Mexico during his career.

But before all that, there was Sheffield and putting a club named Wednesday on the football map.

"Our captain told me to shift from left to right half to stop the outside left. I might as well have tried to stop the wind... ah, Fred was a gem of a player in those days!"

As England captain and one of the finest footballers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Ernest 'Nudger' Needham knew talent, and Spiksley had bags of it.

A slight and silky winger, Spiksley was lightning quick - the "fastest man in football" according to England international team-mate Billy Bassett.

He was a dazzling dribbler - a skill honed through endless childhood practise with a rubber ball in the narrow cobbled streets of Gainsborough. He was peerless in his ability to curl shots and crosses with the outside of his foot, making him a nightmare to defend against. In short, he was a star.

"For a brief period, there is a strong case for putting Spiksley as the greatest forward. In the big games, he was supreme. You read some of the reports from the 1902-03 season and he was unstoppable with his speed," Mark Metcalf, the co-author of 'Flying Over An Olive Grove', a book on Spiksley's life, told BBC Sport.

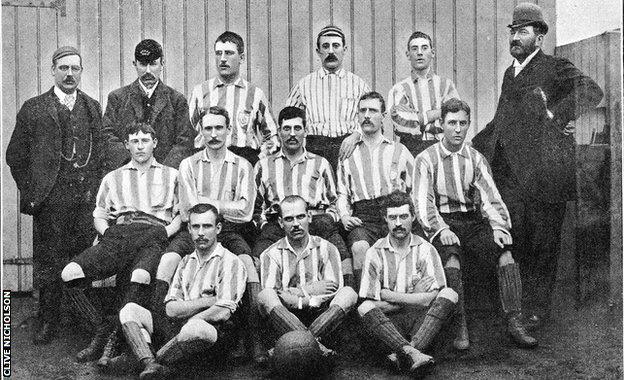

Spiksley (second row, far right) with the Wednesday side in 1891

When Spiksley joined Sheffield Wednesday in 1891 - then known only as Wednesday - they were a non-league club and he an exciting talent with a prolific scoring record. He had scored 131 goals in 126 appearances for hometown club Gainsborough Trinity.

By the time of his departure a decade later, Wednesday were reigning First Division champions, had won the FA Cup for the first time, and Spiksley had added a century of league goals to his name.

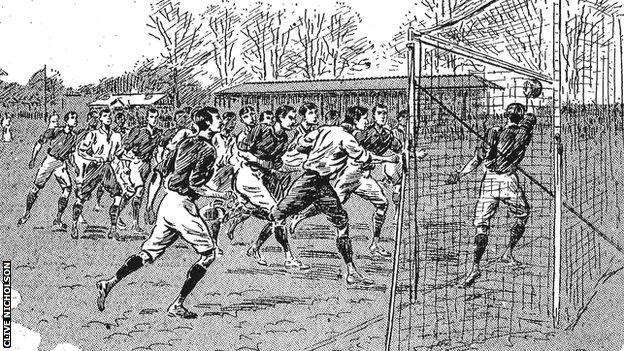

The first of his two strikes that won the 1886 FA Cup final for Wednesday is believed to be the fastest in a final at 20 seconds. He also got the first goal at the club's new Owlerton Stadium which would later become Hillsborough, and his finish in the final game of the 1902-03 season helped seal the league title by one point.

His England career was more sporadic - but eventful nonetheless. There is enough evidence to suggest he was the first England player to score a hat-trick in both of his first two internationals.

In that second match he scored the first treble by an Englishman against Scotland, and was cheered from the touchline at Richmond Park by a barefooted, handkerchief-waving Princess Mary of Teck, who would later marry England's Prince George and become Queen.

Spiksley would add only five more caps and one goal to his international tally over the next five years as a healthy competition for places, favouring of amateur players and then injuries stymied his ambitions.

The physical toll of a career being booted around the pitch by ruthless (and often embarrassed) defenders ultimately ended his association with Wednesday.

Before retiring he would attempt to recapture some of his former glory with the likes of Leeds City, Watford and Southern United. But he never fully recovered from a serious knee injury suffered in a pre-season game in 1903 - the year he left Wednesday.

Little did Spiksley know that this same injury would help keep him out of a brutal war just over a decade later.

An illustration of one Fred Spiksley's goals for England against Scotland

For the majority of England's Football League pioneers, retirement from playing spelt the end of public life. Not so for Spiksley.

While many of his peers took up or returned to less high-profile jobs, he joined the circus, putting his playing skills and fame to good use in theatre impresario Fred Karno's sketch show 'The Football Match'.

The production told the story of a dramatic cup tie between the Midnight Wanderers and Middleton Pie-Cans, with the footballers involved (Spiksley was not the only ex-player to lend his talents) providing authenticity through their ball tricks.

It also provided what may be the first speaking lines for a young actor who Karno described as "pale, puny and sullen-looking" and "looking much too shy to do any good in theatre".

It would be fair to say that Charlie Chaplin soon overcame his shyness to prove Karno laughably wrong.

But while Hollywood and movie stardom called for Chaplin, Spiksley's future would take him across the globe, once again as an advocate for the beautiful game.

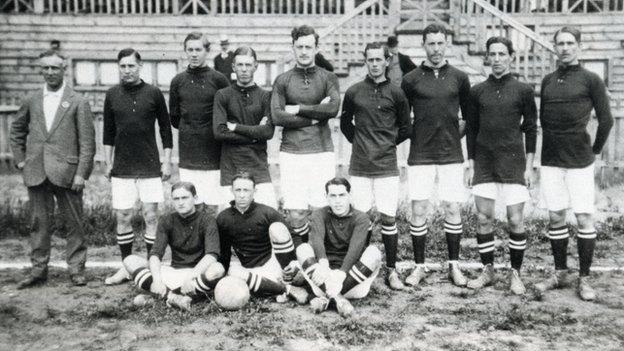

Spiksley (left) during his time as coach of the Sweden national team

Spiksley had been frustrated in previous attempts to get into coaching, missing out on the managerial role at QPR and Tottenham and rejected by Watford because of their fears over his predilection for gambling.

However, seeing the growth of football across the world and the demand for the greater experience and knowledge of English coaches, he spied an opportunity.

The next 20 years would see him move from country to country, across three continents, starting in Sweden and including stints in Germany, France, Switzerland, Belgium, Spain, the United States, Peru and Mexico.

He was particularly impactful in Sweden, where his work with the inexperienced national team resulted in huge improvements and his coaching of AIK Stockholm's players brought them a title in 1911 - an achievement he would repeat in Germany 17 years later with Nuremberg.

English sides seemed unconvinced by his appeal - although Spiksley did have an unsuccessful two-year stint with Fulham towards the end of his coaching career - but fledgling parts of the football world were enthralled by his progressive teachings on technique and the pass-and-move game.

His skill and passion lay in the development of players and he possessed strong opinions on how this should be done, some of which he recorded in Evening News articles and a Pathe News film - believed to be one of the first training videos ever recorded.

In 1914, at the outbreak of the First World War, Spiksley was managing in Nuremberg. A decree was issued to arrest and imprison any foreigners aged between 17 and 45.

Then aged 44, Spiksley and his son, Fred Jr., were locked up. They were beaten and fed on a diet of blackened bread and water.

His wife Ellen was able to secure their release with the assistance of Spiksley's club and the American consul, but they still had to escape Germany to neutral Switzerland, with the added complication that he would be enlisted to fight if decreed fit back home.

The injury to his right knee had ended his playing career, but here it came to his rescue.

When examined, the otherwise fit and healthy Spiksley was able to dislocate the knee (thanks to an early rise that morning and two hours of applying boiling hot water to the joint), leaving him unable to run and, in the eyes of the doctor, unfit for service.

He and his family were able to return to England and he spent the remainder of the war working as a munitions inspector in Sheffield before resuming his coaching career.

Spiksley's final coaching role was working with the students at King Edward VII School in Sheffield, the most successful season of which came in 1933-34 and saw the first XI win all 20 of their fixtures, scoring 181 goals in the process.

Such was the achievement that the Ardath Tobacco Company included King Edward's school team in their football cigarette photograph collection in 1935-36 alongside top professional sides of the time.

Spiksley (left) with the Nuremberg team

But his first and enduring love was the racecourse.

There were some successes with gambling - his family recall him ironing the creases out of a wad of £5 notes he had won at the races and carried back to his home in a suitcase. But the losses were more frequent and often destructive, leading to heavy debts, court appearances and, in 1909, bankruptcy.

There was also a costly divorce from Ellen to deal with later in his life, the reason for which was recorded as his adultery.

"There are plenty of traits of Fred's that were not attractive. He was a gambler and I also suspect his relationship with his first wife was not perfect," says Metcalf.

"In a way, this also must have impacted on how he played on the pitch. He was an outsider. He wasn't necessarily a team player. He didn't live in Sheffield, he continued to live in Gainsborough so maybe wasn't part of that team ethic."

Spiksley's remarkable life saw him shine as one of the finest footballers of his generation and make the unusual leap to the stage before enjoying great success as a coach, despite global conflict and his reputation as a hard gambler and womaniser.

The circumstances of its end were darkly fitting. In 1948, at the age of 78, he collapsed and died from a heart attack on Ladies Day at Goodwood.

Clasped in his hand was an unclaimed winning ticket.