For more than two years, Formula 1 has been preparing a radical rule change in 2021 aimed at making the racing closer.

Last month, a $175m (£141m) budget cap was secured and it was agreed to delay the finalisation of sporting and technical rules until October.

But suddenly, the sands have shifted, and what had appeared to be a refinement process around a generally agreed package now looks anything but.

Over the British Grand Prix weekend, FIA president Jean Todt revealed that the return of refuelling was on the agenda. And a series of other senior figures said that, for the first time, a major focus had shifted on to tyres.

Now, many find tyres boring. And that's not just you, dear reader. A good proportion of the F1 media feel the same way.

But bear with me, because we are going to delve into the very heart of the debate over the future of F1.

Many people in F1 feel that the Pirelli tyres are perhaps the single biggest reason why drivers struggle to race hard and close.

Prime among those are the drivers themselves. After years of trying to change things behind the scenes, they have stepped things up a gear and are subtly exerting pressure, both with public utterances and in private meetings. And it seems to be paying off.

F1's bosses - particularly managing director Ross Brawn - have until recently brushed off questions about the tyres being a major concern. But things are changing.

From apparently not listening, sources say F1 and the FIA have now woken up to this being a serious issue.

Todt, for example, has refused for years to admit publicly that there was an issue with the tyres. But at Silverstone he described the right tyres as "essential", and emphasised the need for the FIA, F1 and Pirelli to work together to make it happen.

And with this, all of a sudden, have arisen all manner of questions about the 2021 rules. Including even whether some of the bigger changes planned might not happen at all.

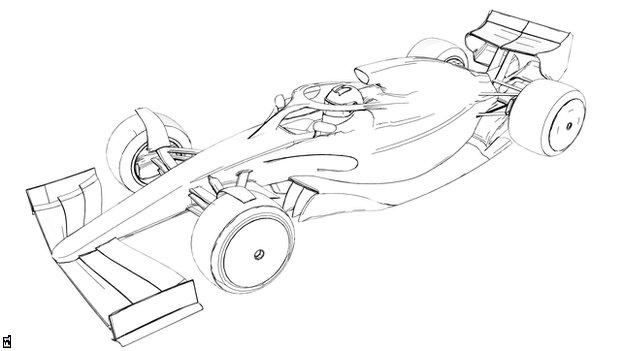

The latest design for the 2021 is called the 'kilo-plus'

There are a number of factors as to why F1 drivers find it so hard to overtake. One is aerodynamics - a car following another encounters disturbed air, which means that it creates less downforce, produces less grip and therefore cannot go as fast in the corners.

But another big influence is tyres, especially when they behave in the way the Pirellis do.

The tyres used in F1 only work in a narrow temperature range, and they are much more prone to overheating when worked hard than previous tyres supplied by other companies. When they overheat, they lose grip and the driver has to fall back to cool them down again. And this happens very quickly, so typically a driver has only a lap or two in 'dirty air' before suffering this problem.

Pirelli has worked on improving this for 2019 - and has succeeded to a degree. But the fundamental characteristic remains.

Here's Lewis Hamilton explaining why he had to back off from attacking Mercedes team-mate Valtteri Bottas after four laps at the British Grand Prix: "If we did not have thermal degradation, I could have just stayed on his tail and kept racing. But I eventually had to give up because after so many laps behind the tyres give up.

"I'm hoping in the future they can make a tyre that goes longer, and you will see closer racing."

Or as one senior engineer put it: "Want to fix racing? Just make tyres that don't saturate behind another car."

Pirelli, to be clear, was asked to produce tyres that had high levels of degradation, although it's a moot point whether the way the tyres behave currently is what was actually meant.

F1 technical chief Pat Symonds, a very experienced engineer who has worked for Benetton, Renault and Williams, said: "We were asking completely the wrong things of Pirelli over the last few years. The high-degradation target was not the way to go."

There is also a political issue with regard to tyres.

A month or so ago, Red Bull were leading a campaign for F1 to reintroduce the tyres used in 2018, because they felt the new 2019 tyres, which have a shallower tread depth and are harder to get up to temperature, were favouring Mercedes, who have dominated the first half of the season.

But a change required 70% of the teams to agree, and when they voted at the Austrian Grand Prix last month, they were split 50-50.

That was that, in terms of the attempt to change tyres this season. But it has highlighted an area of concern for some teams in that Pirelli decides on its own the specification of tyres for a championship season - and once it has, any change requires that 70% agreement, or an intervention by the FIA on safety grounds.

Some teams feel this is wrong - especially because they fear the consequences of individual teams having undue political influence on Pirelli - and want a greater role in the process in the future.

Ferrari team boss Mattia Binotto said: "The process itself may need to be improved because we have no voice on the tyre specification for the season. The only voice we may have is by majority to change them. In there is something that together with the FIA we need to think about."

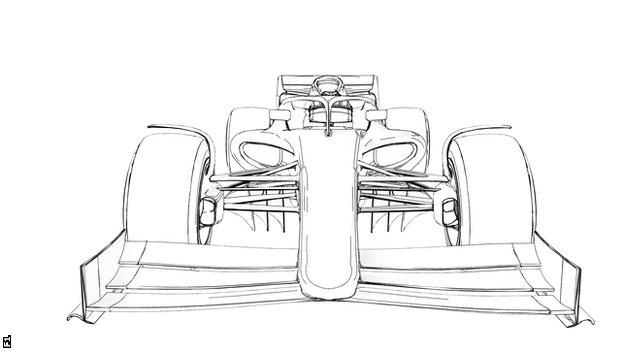

This design is the 11th version of the development of the car

Pirelli says it is prepared to change the tyres if that is what F1 decides it wants.

Its motorsport boss Mario Isola said: "We are happy as always, since day one, to supply tyres that are in line with the targets that F1 decides, provided they are achievable, provided safety is and continues to be the priority."

But he does not agree they are the primary issue.

"We should consider all the package," he said, "which is important, because there is a lot of discussion on the aero package and how it affects the car that is following so the car behind is losing downforce, which means less performance.

"This is irrespective of whether the tyres have degradation or not. If you have less downforce, you lose performance."

The drivers have also recently begun to talk about the cars' weight. This has increased by about 150kg in recent years, primarily as a result of the hybrid engines that have been used since 2014 and all their ancillary parts, such as battery packs and motor-generator units and so on.

The more weight a car has, the harder it is to slow it down and speed it up, the clumsier it feels to drive - and the more energy is transferred to the tyres.

The simplest way to take weight out of the cars would be to dump hybrid engines. But Todt says to go back to plain internal combustion engines in the 21st century is "not possible".

So, how else to make the cars lighter? Take some fuel out at the start of the race. Hence, refuelling.

Todt says he is in favour of a return to a practice last used in 2009, but says he will be led by the results of a study that is being carried out into the pros and cons of refuelling - and a similar one a couple of years ago concluded there were more negatives than positives.

Hamilton again: "It's really hard for Pirelli, with such limited testing, to develop a tyre that can sustain that weight. [You get] thermal 'deg', all these different things. It's like a domino effect.

"With a lighter car, we could fight harder. If you look at the end of the race, we can push more, we can race more at the end without so much of a [tyre] drop-off and that's because the car is lighter on fuel. So (refuelling) might not be such a bad thing for us in the future."

Senior figures accept that refuelling is a sticking-plaster solution that does not address the core issue. The tyres still have their fundamental problem even with hardly any fuel in the car at all - drivers sometimes cannot push flat out throughout a single qualifying lap without overheating them. But it could be a partial fix for a complicated problem.

Refuelling adds cost and when it was last used in the 2000s tended to lead to homogenous strategies and even less overtaking on track.

But proponents argue that it could introduce an extra element of uncertainty - and that it could even be sold on efficiency grounds along with the hybrid engines. The message would be - fuel means weight, and it's more efficient to carry a little fuel as possible in F1, just as it is in your road car.

Brawn has a clear vision for 2021: a more competitive field, with a smaller gap from front to back, especially between the big three and the rest; and cars that can be raced more closely.

The methods by which he is planning to do this are: a new technical formula, in which the aerodynamics mean one car can follow another much more closely; a more equitable prize money distribution; a budget cap; and other methods of cost reduction.

Among the proposals aimed at cost cutting and reducing the gaps between teams are for standard parts in various areas of the car - for example, braking systems and radiators, to name but two.

But some see this plan as counter-productive. They point out that standard parts will inevitably be heavier than those used at the moment because as one senior figure puts it: "The only way to make it cheaper is to make it less good."

The standard brake system being proposed for 2021, for example, is about 10kg heavier than those used by the top teams. Given the number of standard parts being proposed, it is not hard to see how weight could increase significantly as a result of F1's proposals in this area.

And, some point out, why bother? After all, there is a budget cap to keep a lid on costs. Why not just leave it at that?

Binotto said: "We are against the principle of standardisation, unless it brings significant cost saving. But then quality and performance need to be guaranteed."

At Silverstone, F1 made a presentation to selected journalists, including BBC Sport, on progress with the 2021 rules. The latest car design concept was revealed, an artist's representation of which is in this article.

Using a different aerodynamic philosophy, the idea is to ensure that the wake is thrown higher so that a car behind experiences a cleaner airflow. Simulations suggest that from a downforce loss of 35% or more for the following car this year, it will be in the region of 5-10% with the new rules.

That is a significant improvement. But some teams have concerns. One is that the new regulations are very proscriptive and dramatically reduce the amount of design freedom teams have.

The idea is to reduce the disparity between the cars, and limit the gains bigger teams with more resources can make. But Binotto says: "The degree of freedom for aero is something on which we have always been very keen and insisting on the fact that it is important.

"In the objectives of 2021 is that aero has to remain a performance differentiator, and that is the objective we have got."

There are also concerns about the amount of changes that are being made: a completely new aerodynamic concept; standard parts; a change of tyre philosophy, including a move to 18-inch wheels from the current 13-inch wheels, which means much lower profile tyres.

And that's on top of the introduction of a budget cap and potential changes to the format of the race weekend.

Doing so much at once, some argue, increases the risk of something going wrong. Why not fix one problem at a time, starting with the biggest? Which brings us back to the tyres.

At the Silverstone presentation, there was a hint of frustration in Brawn's voice as he detailed the 2021 rule-making process.

He talked about how he had wanted the cost cap introduced in 2020, rather than 2021, so the big teams could not use their existing resources on the new rules, but said this had proved impossible "for various reasons".

He said the development of the current rules had lacked structure and emphasised the amount of work that had gone into the 2021 rules by his team of engineers.

"We've heard some things from the teams," he said, "but we have to ask, why is where we are today the holy position and shouldn't be changed? In my view, it's the wrong position.

"Undoubtedly the teams will have views and comments on some of the decisions. We need to recognise there will be push-back on a number of these things. But there is push-back because they have different objectives. Our objective is to make F1 more sustainable, from a commercial perspective, not just an environmental one."

On complaints that the new rules are too restrictive, he said: "We are being very proscriptive to begin with. Because if we're not, we won't achieve the objectives.

"The complaints the 2021 cars will all look the same - that's already the case [this year]. But there is enough latitude. It's just people won't be two seconds faster; they'll be 0.2secs faster."

But Binotto, boss of F1's most influential and powerful team, clearly has concerns.

"There are still some weeks to make sure that whatever regulation we set for 2021 is a proper one," he said.

"It was good to postpone to October because we felt it was not ready enough. There is a constructive and positive collaboration but the exercise is far from being closed."

The October deadline is only three months away. Time is running out. And where this ends up is anybody's guess.