In 1951, the last time the tournament was played over the Dunluce links, there was just such a moment.

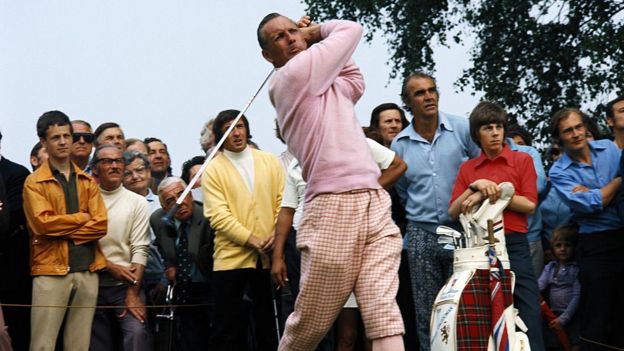

One that would turn Max Faulkner into a household name and not just a golfer known as much for his flamboyant attire as his undoubted talent.

His incredulous playing partner called it "the greatest shot I've ever seen" but had Faulkner's four wood from beside an out-of-bounds fence not sliced to the heart of Royal Portrush's 16th green, Anthony Cerda could have become the first Argentine to win one of golf's four majors.

In the month that he'd celebrate his 35th birthday, Max Faulkner clinched the biggest prize of all.

But it could have been so different.

Golf in the genes

As the eldest son of a professional golfer, it was perhaps no surprise that young Max would follow in the paternal spike marks.

Born in Bexhill-on-Sea in the south east of England, he excelled at several sports but eventually settled on golf and became an assistant to his father Gus.

He once won a junior tournament by 15 shots and was making his mark throughout the 1930s, notably finishing third in the Irish Open at Royal Portrush aged just 21 - an experience he'd draw on 14 years later.But as with so many young men, what might have been Max's best years were lost to the war.

Between 1939 and 1945 he barely lifted a club, instead becoming a services boxing champ and honing the granite physique that powered his swing.

A wartime epiphany

While stationed in Liverpool as a Royal Air Force physical training instructor, a doodlebug landed near Max, perforating his eardrums and leading to a spell laid up in hospital.

The war would bring family heartache too, with the loss of his younger brother Frank in a road accident - both events shaping the future champion more than he'd realise.

Max recalled: "Every morning the nurses brought pretty flowers into the ward and every night they took them out.

"It was so grey without those flowers and I thought: 'If I ever get out of this bloody war I'm going to wear some colours.'"

Faulkner cut a dash on the golf course in his colourful attire

As good as his word, he returned to tournament play a riot of glorious technicolor - pinks, yellows and peacock blues making him stand out in an age when professional golfers were expected to know their place and amateurs were the game's "gentlemen".

But even in his greatest triumph, there were those who saw fit to snipe.

Reporting on his Open win, Leonard Crawley wrote in The Daily Telegraph: "Faulkner is highly strung. He has tried to hide this very human weakness by dressing himself in gaudy colours and pretending to play the fool."

A pastel premonition

Not that the dapper dandy who lit up the links long before Ian Poulter gave a damn.

By the time he rocked up at Royal Portrush in his pastel hues and two-tone shoes, Max was fulfilling the potential curtailed by the war and had a premonition.

"As soon as I arrived I knew something big was about to happen. For the whole of that fortnight I seemed to be living in a different world from everyone else," he said.

"The Open is one tournament you can't win suddenly from out of the blue. In 1949 I had been tying with one round to go and in 1950 I had been one behind with one round to go."

In 1951 an unfathomable conviction and a red-hot putter took Max to the title, as he himself explained: "It was almost laughable. Wherever I was I couldn't seem to do anything else but put it in the hole."

Faulkner was handed the Claret Jug in 1951, later saying it "was all I ever wanted"

His putting showcase was enough to secure a six-shot lead heading into the final round on Friday afternoon and led to an ill-judged tempting of fate he thankfully didn't live to regret.

Lost in his own thoughts as he prepared to tee off, a young boy asked Max to sign his ball.

At first hesitant, he relented when the youngster told him he was going to win.

"I asked him for a pen. I put 'Max Faulkner. Open Champion 1951' and then looked at it before giving it back.

"As I walked to the tee it kept appearing in front of me: 'Open Champion 1951. Open Champion 1951.'

"It certainly looked good."

Three nerve-shredding hours later, what he'd written was etched on the Claret Jug.

"It was all I ever wanted. The Open meant everything to me," reflected Max.

Fuelled by tea and the cigarettes he smoked throughout his life, Max still could still play nine holes in 36 strokes until a few years before his death at the age of 88 in 2005.

A more than solid career yielded 19 professional titles and five Ryder Cup appearances but he'd never again taste major glory after 1951.

Indeed, after missing a short putt during the following year's championship at Royal Lytham he knew he would never win it again.

"Somehow the desire had gone."

info@businessghana.com

info@businessghana.com