Cameroonian scientist Marie Makuate has been at the forefront of using information harvested by satellites to help save the lives of people on Earth in emergencies, but she argues the expense of the data should spur more African countries to launch their own space hardware.

In the hours after the deadly earthquake struck central Morocco last September, the 32-year-old's phone started buzzing.

She was thousands of kilometres from the zone of destruction, but her skills analysing satellite images were vital.

"I woke up hearing message notifications of my colleagues telling me that there had been a disaster in Morocco," Ms Makuate tells the BBC from her base in the Cameroonian capital, Yaoundé.

As a geospatial expert for the NGO Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team, she creates maps to help emergency services navigate an unpredictable territory so that people in need can be reached quickly.

It is a job that Ms Makuate says gives her purpose and motivation.

"I was shocked to hear about the [Morocco] disaster, but then I thought that if I mapped as much infrastructure as possible, it would help other people save lives."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSeptember's earthquake in Morocco destroyed villages and left more than 2,900 people dead

Last September, her maps, derived from open-source, freely available images, became a lifeline for organisations like Médecins Sans Frontières operating in the devastated towns, which included Marrakesh.

A map of the kind that Ms Makuate creates looks very different from the ones that most might be familiar with.

It shows an updated, high-definition view of the territory to which she and the team she leads add potentially life-saving information.

"The most important thing emergency services need to know when there is a disaster is: 'Where is the road? where is the water? where's a river or a [shopping] mall?'" Ms Makuate says.

But due to the costs associated with launching and maintaining a satellite in orbit, the images that geospatial analysts rely on can be expensive, especially when they are required at short notice, as in the case of natural disasters.

"When an emergency starts, I have to ask around our satellite partners to see who is offering the best-quality images for free."

Some satellite companies do offer free imaging for disaster-relief purposes, but help is often limited in scope and time.

"For example in the case of Morocco, we had access to images of only a specific area, and after we were done, we could not access them any more."

Morocco does have its own satellites, but Ms Makuate makes the case that more African countries should be sending them into space and make their output more freely available.

This is not just about emergencies. Satellite imagery can help, among other things, in boosting agriculture, analysing population changes and understanding what is happening to natural resources such as water.

"If a country has its own satellite, it doesn't have to pay for the images," says the young scientist.

Satellite images can cost up to $25 (£20) per square kilometre - getting high-definition photographs of an area the size of Lagos, for example, would cost more than $80,000.

Ms Makuate has been making her case for more pan-African collaboration in front of a group of industry specialists that came together this week in Angola's capital, Luanda, for the NewSpace Africa Conference.

The meeting gathered investors and experts in how space technology can help the continent.

There is huge potential in the African space sector - it is expected to be worth more than $20bn by 2026, according to consultancy firm Space in Africa. But the vast majority of this money is coming from outside the continent - through companies who are selling services to Africans.

"Imagine if we can just take 10% of that share and invest it in African companies," says Dr Zolana João, the general manager of the Angolan National Space Programme.

He, like Ms Makuate, believes that greater investment within the continent will better serve African governments, which are often hampered by a lack of reliable data.

"If I can map very precisely and in quantified ways important sectors of the country, I can then relay this [data] to the government so they can reach better decision-making," says Dr João.

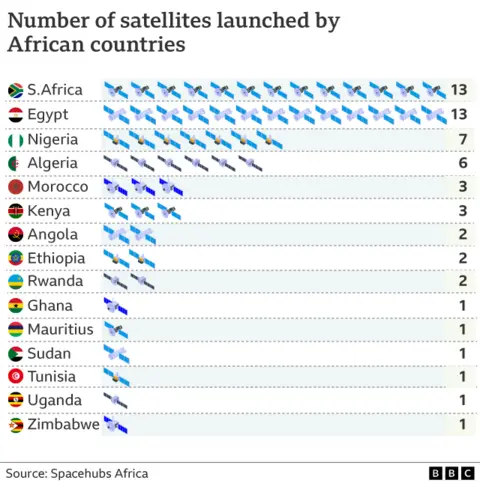

South Africa and Egypt are the African countries with the highest number of satellites in orbit - both with 13 each - according to consultancy firm Spacehubs Africa. By comparison, a 2022 survey published in Forbes magazine said the US had more than 3,400.

South Africa uses its satellites to monitor the impact of mining activities as well as help provide consistent internet and telephone coverage, according to Ms Makuate.

In the case of Egypt, investment in telecommunication satellites reflects the country's position as a media powerhouse across the Arabic-speaking region.

Investment aside, the most fundamental obstacle in the way of Africa's space ambition is access to education.

"That is our weakest link when it comes to implementing space programmes in Africa," says Dr João.

That is a task that Ms Makuate is ready to take on.

In 2019, she took a master's degree in geomatics from the African Regional Centre for Space Science and Technology based in Nigeria's Osun state.

"In Cameroon there wasn't this programme, so when I came back from Nigeria I wanted everyone to know about it," Ms Makuate says.

But attending the course also showed her how small the presence of African women in this scientific field was.

"In a class of 35 we were three women, the year after they told me they had one or two women."

Marie Makuate

Marie MakuateAs part of her training work, Marie Makuate shows students how to use surveying equipment

It was the spark that motivated her to found Geospatial Girls and Kids, an association that offers free professional training in geospatial science to young women in Cameroon and Ivory Coast.

"It's easier for us to be inspired by women than by men because when you see women on a panel, it inspires you to do the same next time."

At the end of the course, students receive a certificate and are connected to potential employers.

Three of Ms Makuate's students are now employed as geospatial analysts and data collectors.

She says motivating her students can be hard, but also rewarding.

"Students say I'm strict with them, but at the end of the training they are happy because I pushed them beyond their limits."

She wants to create the next generation of experts who can analyse satellite imagery, who she hopes will be able to work with data generated by equipment sent into space by African governments.