The arrest and expected extradition of Julian Assange has set into motion what could prove to be the most important free speech and free press case in our history. Or not.

Assange has been charged with a single count of participating in the hacking of intelligence computers with Chelsea Manning to reveal controversial intelligence operations in the United States.

For many, Assange is a journalist, a whistleblower, a hero. Yet for others in Washington, he is the man who embarrassed the establishment in Congress, the intelligence community and even the media.

Those powerful foes are likely to bring considerable pressure to deny Assange a platform for highlighting the operations that led to massive civilian losses and undisclosed military strikes, the very type of information disclosed in the celebrating "Pentagon Papers" case involving the New York Times in the Vietnam War.

For historians in both Great Britain and the United States, there should be something eerily familiar in this controversy.

Almost 300 years ago, the foundations for American protections of the free press were laid in the trial of John Peter Zenger.

The case has striking similarities to the pending prosecution of the Wikileaks founder.In the case, the recently installed British governor William Cosby was the subject of an anonymous pamphlet that detailed his many abusive and corrupt practices in New York and New Jersey, from stealing Indian lands to pilfering the Treasury to rigging elections.

Cosby ordered four editions of the Zenger's New York Weekly Journal publicly burned and arrested Zenger. He then installed a biased judge who held Zenger's defence lawyer in contempt.

Despite using every means to punish Zenger for what Cosby called "scandalous, virulent, false and seditious reflections", the colonial jurors balked and acquitted him.

The trial of Peter Zenger in New York in 1734 in which the printer was accused of libel

It was the defining moment for the colonies and ultimately led to far stronger protections of journalists in the United States than in Britain, as embodied in the first amendment to the US constitution declaring that "Congress shall make no law... abridging the freedom... of the press."

Much has changed in the United States for the press, but perhaps not as much as we claim.

The Justice Department crafted the charge to evade the constitutional concerns over the prosecution - and the unresolved status of Assange.

By alleging that Assange was given a password and helped set up a cloud for Manning to share the data, the government is charging him not with the distribution of the material but actively participating in its theft.

However, the unsealed indictment in Alexandria, Virginia, is remarkably thin on evidence that Assange played such an active role or used the password in question.

Setting up a cloud for sharing information can easily be viewed as simply facilitating the anonymous disclosure from a source. Where reporters once arranged for drop spots, there are now digital equivalents for such exchanges.

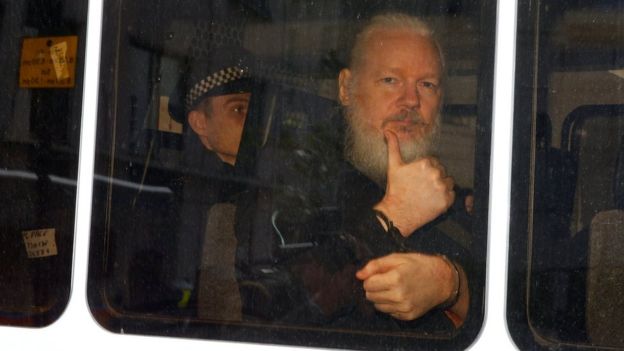

Assange gave a thumbs-up as he was taken to a London courthouse

Rather than exploring reasons and effort to reveal controversial intelligence operations, Assange could be forced to confine his defence to the more mundane charge of "computer intrusion".

Yet, the indictment is conspicuously thin on the evidence of that role. The government alleges that Manning gave "a portion" of a password "to crack" which "was stored as a 'hash value' in a computer file that was accessible only by users with administrative-level privileges".

However, the government then says not that Assange arranged to crack the code but only that "cracking the password would have allowed Manning to log onto the computers under a username that did not belong to her".

Such a measure would have made it more difficult for investigators to identify Manning as the source of disclosures of classified information.

A van supporting Manning and Assange seen in London last week.

Assange is likely to face more charges once he is in the United States.

A superseding indictment might encompass the role Wikileaks played in publishing emails stolen from the Democratic Party during the 2016 election campaign.

Special Counsel Robert Mueller indicted 12 Russian military intelligence officers for their part in the hack and alluded to Wikileaks in those indictments, although not by name.

However, thus far, no Americans have been indicted for any alleged conspiracy with the Russians and, putting aside the narrative, Assange is so far being prosecuted for the same type of conduct as people messing with Netflix passwords.

But for now, the US only wants to show under extradition laws that there is a reasonable basis for believing that Assange committed a crime in the United States. The government also wants to avoid any criminal charge that could result in the death penalty.

Nevertheless, the Justice Department is likely to do what the British government failed to do with Zenger.

It will focus its charges on insular acts like sharing passwords or hacking. By doing so, the government can file a motion (what's called a motion in limine) to prevent Assange from raising his motivations or the disclosure of the secret operations.

It could be declared immaterial. The jury will not hear the type of evidence that Zenger's lawyers forced into his trial. Assange would look simply like some slightly creepy-looking Australian hacker.

Activists at a 2011 rally to free Manning

US Attorney Tracey McCormick in Virginia could succeed if she keeps any counts focused on such technical and narrow acts.

It would be like reducing the whole of Macbeth to the final scene where Macduff beheads the King, and therefore revealing nothing about his motivation or history.

Reduced to Act V, Macduff simply looks like a blood-soaked regicidal maniac, rather than an avenging hero saving the country from a tyrannical leader.

To paraphrase Shakespeare, Wikileaks could not be vanquished until the Great Assange came to Capitol Hill.

He is now likely on his way and the trial could make the Zenger trial look like a model of transparency and accuracy.