The Islamist militant group Boko Haram has been active in north-eastern Nigeria for well over a decade.

President Buhari says its activities have been largely brought under control since he assumed office in 2015.

His political opponents disagree and say the situation has recently deteriorated both in terms of the number of attacks and kidnappings by the group.

Ahead of Nigeria's elections on 16 February, BBC Reality Check examines the competing claims over the security situation in the country.

Formed around 2002 as a non-violent organisation with the aim of purifying Islam in northern Nigeria, it became increasingly radicalised and eventually adopted militant tactics in pursuit of its aims.

It has been active not only in Nigeria, but also in the neighbouring countries of Chad, Niger and Cameroon.

Tens of thousands of civilians have been killed and more than two million displaced over the past decade.

Boko Haram has been notorious for kidnapping schoolchildren and attracted global media attention in 2014 following the abduction of almost 300 girls from a school in the town of Chibok, in Borno, the state where the militant group has been most active.

In 2015, Boko Haram was ranked the world's deadliest terror group by the Institute for Economics and Peace.

Since then, territory controlled by the group has declined and it has splintered into competing factions.

However, the Islamist militants remain active in the region, defying attempts by the army to bring the insurgency to an end.

To underline this continued activity, in 2018 more than 100 schoolgirls were kidnapped from the northern town of Dapchi. Most of the girls were eventually released.

The former Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo, who is supporting main opposition candidate, Atiku Abubakar, has strongly criticised President Muhammadu Buhari's record on tackling Boko Haram.

"The security situation has deteriorated, with kidnapping everywhere," said Mr Obasanjo in January.

But President Buhari's view of the security situation is very different. He says the militants have been "decimated" since 2015 in their stronghold of Borno State.

So what are the available facts regarding both attacks on civilians and on kidnappings?

More than two million people have been internally displaced by Boko Haram, according to the UNHCR

Insecurity and poor communications in rural areas make assessment both for the government and independent organisations particularly difficult and many incidents go unreported.

The Nigerian government's National Bureau of Statistics provides public access to economic, social and general security data gathered within Nigeria but a spokesman told BBC News it did not collect data on the activities of Boko Haram.

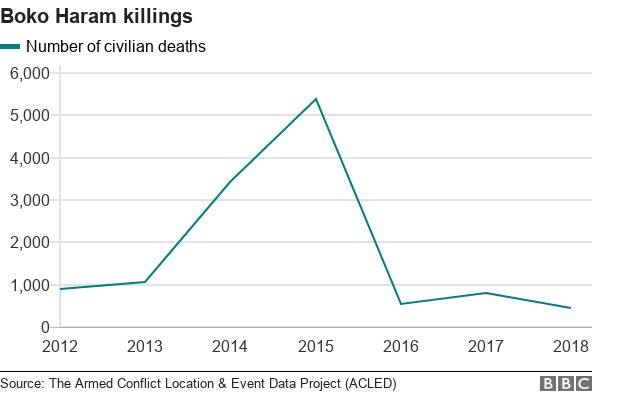

However, research by the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) tracks information by monitoring local media and other reports.

From a peak in 2015 of more than 5,000, the number of deaths attributed to Boko Haram has fallen off significantly to below 1,000 a year for the past three years.

This decline followed a military campaign launched against Boko Haram in 2015 by the Nigerian government, with international support.

Large areas of territory previously controlled by Boko Haram were recaptured during this offensive.

So, President Buhari is right to say killings by militants have declined substantially since he came to office in 2015.

But these attacks have not ended completely and there have been several in the early weeks of 2019.

"In terms of the current situation, I do think the current trend line is quite dangerous and that they are far from defeated," says Alex Thurston, a visiting assistant professor of political science and comparative religion at Miami University of Ohio.

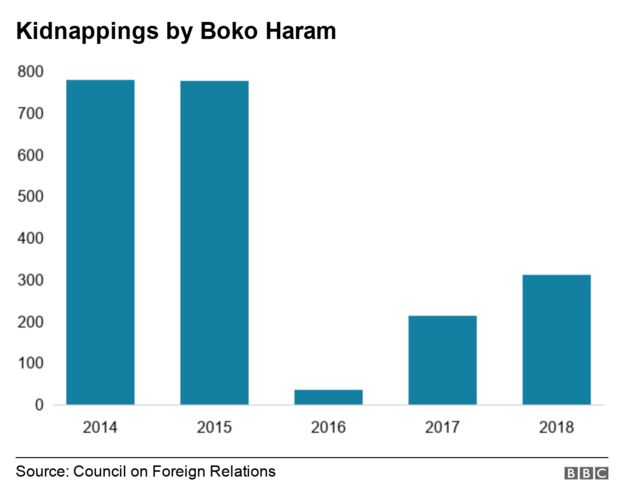

The Nigeria Security Tracker, used by the Council of Foreign Relations (CFR), in Washington, monitors kidnappings through local media reports.

These indicate a peak in the number of kidnappings in 2014 and 2015, when Boko Haram was at its strongest militarily.

However, despite a dramatic fall in reported kidnappings in 2016, the level has risen since then, with 310 reported last year.

One theory put forward for this increase is that as Boko Haram has lost territory and military influence, its tactics have shifted away from direct confrontation with security forces.

Instead, the militants have turned their attention to soft targets such as schools and rural villages, taking hostages from these locations.

So, when Mr Obasanjo says "the security situation has deteriorated with kidnapping everywhere", he's right in the sense that the level of kidnapping is on the increase and that major incidents such as the kidnapping of more than 100 schoolgirls in Dapchi, in 2018, do give serious cause for concern.

This fear is particularly heightened given Boko Haram's use of children as suicide bombers. In 2017 and 2018, there were 77 and 26 incidences respectively of children being used in this way by the militants. In 2016 this figure was nine, according to Unicef.

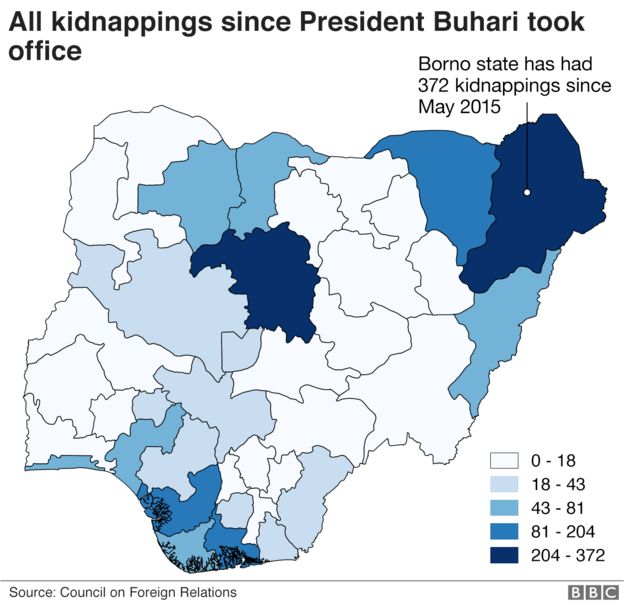

Looking at the distribution of all kidnappings across Nigeria, this is clearly not the case, with Boko Haram operating largely in the far north-east of the country.

Kidnappings have also been regularly reported in the country's oil-rich southern Niger Delta region - but these are unrelated to the activities of Boko Haram.

So, looking at the overall picture of kidnappings, not just by Boko Haram, you can see that the distribution is more geographically widespread - but it's certainly not the case as Mr Obasanjo says that kidnappings have been taking place "everywhere" across the country.

Overall, the picture of Boko Haram activity in the north-east of Nigeria appears to be one of declining military activity.

But along with this has come a recent rise in kidnappings although it's not clear whether this indicates a resurgence in the strength of the group or a re-focusing on softer targets.