An Australian court has found a Catholic archbishop guilty of concealing child sexual abuse in the 1970s.

Philip Wilson, now archbishop of Adelaide, becomes the most senior Catholic in the world to be charged and convicted of the offence.

He was found to have covered up the abuse of altar boys by a paedophile priest colleague in New South Wales.

During his trial he denied being told about the abuse by some of the victims.

Wilson will be sentenced in June and faces a maximum two-year jail term.

Last month, Wilson told the Newcastle Local Court he had no knowledge of priest James Fletcher's actions, which took place when he was an assistant priest in Maitland, 130km (80 miles) north of Sydney.

Fletcher was later convicted of nine child sexual abuse charges in 2004, and died in jail in 2006.

One of his victims, former altar boy Peter Creigh, told the court he had described the abuse to Wilson in detail in 1976, five years after it took place.

Peter Creigh testified that he had told Wilson about being abused

Magistrate Robert Stone rejected Wilson's claims that he had no memory of the conversation, and said he had found Mr Creigh to be a reliable witness.

The priest knew "what he was hearing was a credible allegation and the accused wanted to protect the Church and its reputation", Magistrate Stone said.

Another victim, who cannot be named, told the court he disclosed the abuse in the confessional box when he was 11 years old.

He said Wilson told him he was telling lies and to recite 10 Hail Mary prayers as punishment.

In a statement issued by the Church on Wednesday, Wilson said he was "obviously disappointed" with the verdict and would consider his legal options.

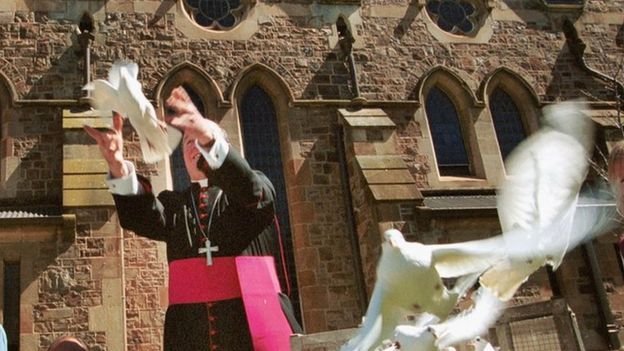

Archbishop of Adelaide Philip Wilson outside the city's cathedral in 2002

His lawyers had tried to get the case thrown out on four occasions, after the 67-year-old was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease.

Child sexual abuse survivors praised the verdict in emotional scenes outside the court following the decision.

"The decision will hopefully unravel the hypocrisy, the deceit and the abuse of power and trust that the Church has displayed," Mr Creigh told reporters.

In 2012, then PM Julia Gillard set up a royal commission, the country's highest form of public inquiry, to look into institutional responses to child sexual abuse.

By the time it had published its final report in December last year, it had handled 42,000 calls and referred more than 2,500 cases to the authorities.

It said institutions including churches, schools and sports clubs had "seriously failed" to protect children.

Catholic institutions came in for particular criticism. The president of the Australian Catholic Bishops Conference, Archbishop Denis Hart, offered an "unconditional" apology.

PM Malcolm Turnbull said "a national tragedy" had been exposed.

The first cases of molestation by priests came to light in the 1980s. In the 1990s, revelations began of widespread abuse in Ireland, with cases spreading to more than a dozen countries this century.

Ireland, the US and Australia have carried out national inquiries, and there have been cover-up scandals such as in the Archdiocese of Boston in the US.

Although there have been convictions of priests for sexual abuse, in many cases accused clergymen were either moved or retired by their Church, with financial settlements agreed in some cases, particularly in the US.

Victims rights groups have complained the convictions do not often extend beyond priest level, with few senior figures brought to account, although a number have left their positions over their actions in sexual abuse cases, including Cardinal Bernard Law in Boston.

One of the most high-profile recent cases has been in Chile. All of its 34 Catholic bishops offered to resign. Pope Francis had handed them a 10-page document accusing Chile's Church hierarchy of negligence in sexual abuse cases.