A century ago, new restrictions on selling alcohol left US wine merchants reeling.

Now President Donald Trump's decision to raise taxes on European wine imports to 100% presents a similar threat, the industry says.

Wine sellers are warning that their businesses will not survive if the tariffs go ahead.

They want Washington to drop the proposal, which is in retaliation over European subsidies for Airbus.

The industry says raising the tariffs, on top of an earlier increase, will lead to job losses and price increases in the US.

"It is without hyperbole that I tell you that the proposed tariffs would be the greatest threat to the wine and spirits industry since Prohibition, in 1919," says Benjamin Aneff, managing partner of Tribeca Wine Merchants.

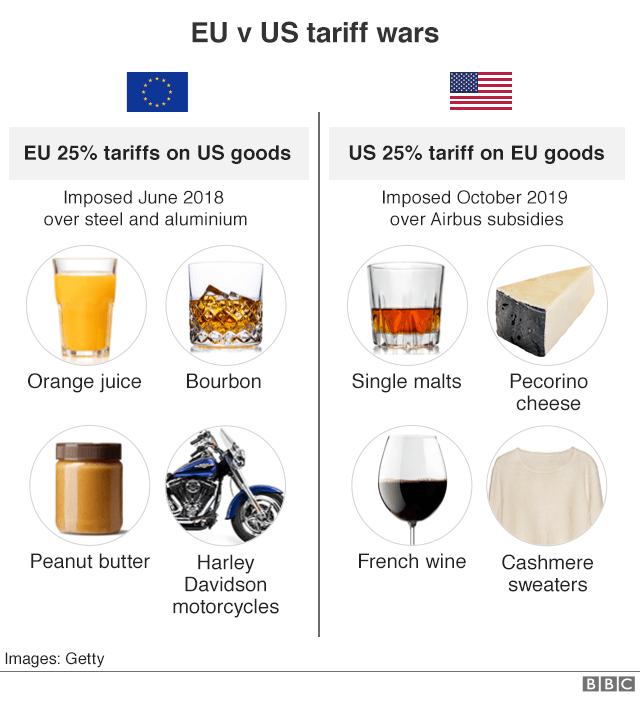

The US imports about $5bn (£3.8bn) in wine from Europe a year. But since October, the industry has been grappling with a 25% tax on European wines, which the US imposed after winning approval from the World Trade Organisation to retaliate in the dispute overs subsidies to planemaker Airbus.

Most American sellers managed to absorb the impact of the first round of tariffs. But they say if the US strikes again, with a 100% tax, it will disrupt the industry, invite retaliation and place thousands of jobs at risk.

For American drinkers, the National Association of Wine Retailers estimates that prices would more than double and some bottles will simply become too expensive to import.

Thousands of people have opposed the move in written comments to the US Trade Representative, which handles the decision and is accepting submissions until 13 January.

"These tariffs are intended to be punitive measures against European countries, but instead, they are having a calamitous impact on American small businesses, American workers, and American consumers," wrote the heads of Field Blend Solutions, a New York-based importer.

The Trump administration might have assumed it could target fine Burgundies without causing too many political problems, shrugging off a bit of an outcry in Francophile circles.

But Robert Tobiassen, president of the National Association of Beverage Importers, says that kind of thinking "misses the point".

"It's not just a question of simply raising prices. It's a question of what is the impact on jobs, what is the impact on the US marketplace," he says.

A lot of the frustration is about the "asymmetric approach", he adds. "Why is wine having to pay for a dispute on civil aircraft?"

In December, the US said raising the tariff up to 100% was necessary, because of "lack of progress" on resolving the subsidy fight. Brussels, however, has maintained that the US has not been interested in negotiating.

Last month, Donald Trump said he thought the two sides would be able to "work it out". But Mr Trump, who is not a wine drinker, has also dismissed US concerns, saying Americans could substitute home-grown bottles. (His family owns a winery in Virginia.)

But even California growers have spoken out against the tariffs, arguing that they may spark retaliation, without convincing people to buy American.

"If they do go to another wine, would they go to Chilean wine or South African or New Zealand?" Mr Tobiassen says.

Tom Wark, executive director of the National Association of Wine Retailers, says the administration may back down from the full 100% threat - but he thinks some tariffs on wine remain likely.

Indeed, champagne is facing possible tariffs in a separate fight over France's new tax on technology firms.

"The American wine industry appears to be the industry that people are willing to punish," says Mr Wark.