Wage growth beat market and economist expectations in the three months to April.

Pay rose by 3.4% compared with a year ago. After taking inflation into account, wage growth was 1.4%, official figures show.

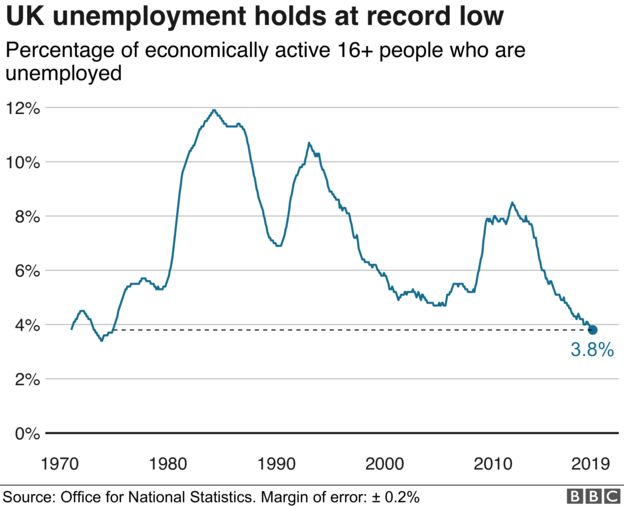

The unemployment rate remained at 3.8%, and has not been lower since the October to December 1974 period, the Office for National Statistics said.

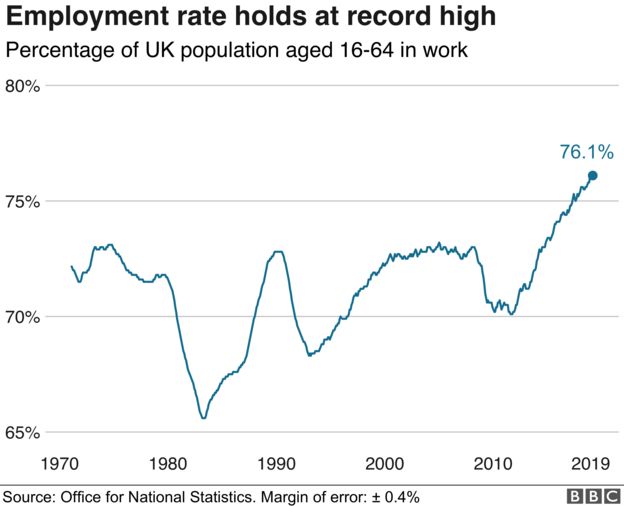

The employment rate for women was 72%, the highest on record.

This is after changes to the state pension age leading to fewer women retiring between the ages of 60 and 65.

Matt Hughes, deputy head of labour market statistics at the ONS, said: "With employment growth among women coming from full-timers, the overall gap between men and women in hours worked is now the lowest ever - women now average about three-quarters of men's weekly hours, compared with around two-thirds 25 years ago."

And PwC chief economist John Hawksworth said it was "interesting" that female employment rose by 60,000 compared with the previous quarter, while male employment fell by 27,000.

"This is consistent with a longer-term trend towards a narrowing gender employment gap.

"Male employment is still higher at around 80%, but this is well below its historical highs of over 90% back in the 1970s."

Tej Parikh, chief economist at the Institute of Directors, said: "The buoyant labour market is still going strong for the UK economy, even as it weathers widespread political uncertainty."

"However, the employment boom cannot last forever, and is certainly showing signs of softening."

How is it that employment has reached record levels yet people aren't feeling that in their pockets? It's a question that has confounded labour market experts.

But with 357,000 jobs having been created over the last year, overwhelmingly full-time, companies are now having to pay a higher price to attract staff.

Wages across the economy grew by 3.4% in the three months to April, compared with a year ago, according to the Office for National Statistics, with the biggest increases in the construction and financial services industries.

Strip out inflation, however, and real wages remain on average a touch below pre-financial crisis levels.

What happens next? The rate of job creation is slowing, and economists are divided over whether this represents more caution on the part of employers or a lack of suitable candidates.

If it's the former, then the rate of pay growth could moderate. But if it's the latter, then salaries may rise faster as firms compete for the best talent.

But bumper pay rises could come at a cost. The Bank of England is known to be concerned that faster pay growth could equal higher inflation, which could mean it's more inclined to raise interest rates.