One of the most comprehensive studies of the state of banking and markets since the financial crisis warns that "dangerous undercurrents" are a rising threat to the world economy.

The International Monetary Fund's Financial Stability Report says that although banks are far safer than they were in 2008 there are new risks.

Trade tensions are growing, the IMF says, and inequality has risen.

Further moves towards a trade war could "significantly harm global growth".

Other threats to trade, such as a disorderly Brexit, could also "adversely affect market sentiment", the IMF argues.

The US-based organisation says that a "no-deal" departure from the European Union could lead to fragmentation in European money markets, meaning that finance cannot flow around the system so efficiently.

The body urges the Bank of England to be ready to provide more quantitative easing - money printing - if it is required.

In a separate report, the IMF said the UK had historically weak public finances with high levels of debt and low levels of assets. Britain sold off many of its assets in the privatisations of the 1980s and 1990s and also did not create a sovereign wealth fund from its oil revenues, which Norway did.

Of leading industrialised countries, only Portugal's "net worth" was in a poorer position, the IMF said.

That could mean that Britain will have to raise more taxes in the future because government-owned asset growth will not provide as much support to the economy.

The Financial Stability Report is the second time in 24 hours the IMF has published sober warnings about the state of global finance.

On Monday, it downgraded world growth forecasts for next year, blaming new trade barriers.

Tuesday's report says governments should resist attempts to roll back banking regulations put in place in 2008 to stop a similar financial crisis happening again.

Complacent

President Donald Trump has already pushed through laws repealing banking rules in America for smaller institutions, saying they were holding back bank lending to businesses.

The IMF also warns market investors, who have seen the largest upward bull run in stocks in history.

The report says they are in danger of becoming complacent about the chances of an economic shock to the system.

One could be the ending of "easy money".

Central banks are starting to withdraw the stimulus that was put in place at the time of the financial crisis.

Interest rates are rising and quantitative easing - money printing - being dialled back.

The IMF fears this could lead to sharp falls in markets.

The risks of a government funding crisis in Italy, where the country's banks are under pressure, is also highlighted.

Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte thinks the IMF's forecasts for Italy should be revised in light of its new budget

"Looking ahead, clouds appear on the horizon," the report, published at the body's annual meeting in Bali, Indonesia, says.

"Support for multilateralism has been waning, a dangerous undercurrent that may undermine confidence in policymakers' ability to respond to future crises.

"Nonetheless, despite trade tensions and continued monetary policy normalisation in a few advanced economies, global financial markets have remained buoyant and appear complacent about the risk of a sudden, sharp tightening in financial conditions."

The IMF's warnings will increase fears that the present buoyancy in global growth may not last.

The American economy has been performing strongly, encouraging international investors to move capital there and invest in the dollar.

To cool inflationary pressure, the American central bank, the Federal Reserve, is raising interest rates, which acts as a further attraction to global capital because returns are higher.

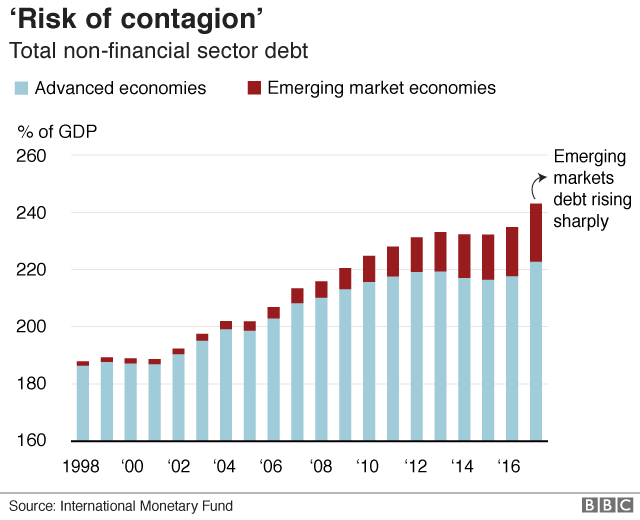

That puts pressure on emerging market economies such as Turkey and Argentina, which have large amounts of debt which concerns investors.

The IMF says there is a "risk of contagion" as investors become increasingly nervous about the strength of emerging markets, with the risk of capital flows towards the US accelerating.

The report says that outflows could hit $100bn (£76.4bn) over a year, about 0.6% of emerging market economies' gross national income.

That would be "of a magnitude" similar to the financial crisis.