Allegations that research firm Cambridge Analytica misused the data of 50 million Facebook users have reopened the debate about how information on the social network is shared and with whom.

Data is like oil to Facebook - it is what brings advertisers to the platform, who in turn make it money.

And there is no question that Facebook has the ability to build detailed and sophisticated profiles on users' likes, dislikes, lifestyles and political leanings.

The bigger question becomes - what does it share with others and what can users do to regain control of their information?

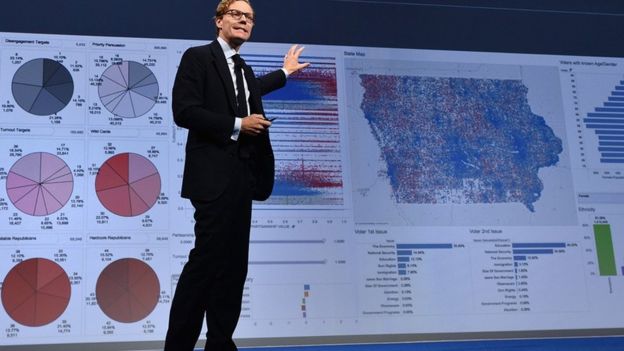

Cambridge Analytica chief executive Alexander Nix told MPs it used data from "Facebook surveys"

We've all seen these quizzes - offering to test your IQ, reveal your inner personality, or show you what you'd look like if you were a glamorous actor.

It was information from one such Facebook quiz - This is Your Digital Life - that Cambridge Analytica is alleged to have used to harvest the data of millions of people.

Many such quizzes come with reassurances that your data is safe.

These games and quizzes are designed to tempt users in but they are often just a shop front for mass data collection - and one that Facebook's terms and conditions allow.

Privacy advocates Electronic Frontier Foundation said the way these quizzes collected data reflected "how Facebook's terms of service and API were structured at the time".

Facebook has changed its terms and conditions to cut down on the information that third parties can collect, specifically stopping them from accessing data about users' friends.

It is not yet clear exactly what information the firm got hold of - this is now subject to an investigation by the UK data protection authority, the ICO.

This will mean that you won't be able to use third-party sites on Facebook and if that is is a step too far, there is a way of limiting the personal information accessible by apps while still using them:

Digital fingerprints are getting bigger as people share more information online

There are some others pieces of advice too.

"Never click on a 'like' button on a product service page and if you want to play these games and quizzes, don't log in through Facebook but go directly to the site," said Paul Bernal, a lecturer in Information Technology, Intellectual Property and Media Law in the University of East Anglia School of Law.

"Using Facebook Login is easy but doing so, grants the app's developer access to a range of information from their Facebook profiles," he added.

There really is only one way to make sure your data remains entirely private, thinks Dr Bernal. "Leave Facebook."

"The incentive Facebook will have to protect people more will only come if people start leaving. Currently it has very little incentive to change," he told the BBC.

It seems he is not alone in his call - the hashtag #DeleteFacebook is now trending on Twitter in the wake of the Cambridge Analytica scandal.

But Dr Bernal acknowledges that it is unlikely many will quit - especially those who see Facebook as "part of the infrastructure of their lives".

Mr Schrems has been involved in a series of complaints against Facebook since 2011

Under current data protection rules, users can make a Subject Access Request to individual firms to find out how much information they have on them.

When Austrian privacy advocate Max Schrems made such a request to Facebook in 2011, he was given a CD with 1,200 files stored on it.

He found that the social network kept records of all the IP addresses of machines he used to access the site, a full history of messages and chats, his location and even items that he thought he had deleted, such as messages, status updates and wall posts.

But in a world where Facebook information is shared more widely with third parties, making such a request gets harder.

As Dr Bernal says: "How do you ask for your data when you don't know who to ask?"

That is likely to change this summer with the introduction in Europe of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which aims to make it far easier for users to take back control of their data.

The threat of big fines for firms that do not comply with such requests could make it more likely that they will share this information, which must be given to consumers "in a clear and readable form".

Can you remove your profile from social media?

Data protection laws in Europe suggest that firms should only keep user data "as long as necessary" but the interpretation of this can be very flexible.

In Facebook's case, this means that as long as the person posting something does not delete it, it will remain online indefinitely.

Users can delete their accounts, which in theory will "kill" all their past posts but Facebook encourages those who wish to take a break from the social network simply to deactivate them, in case they wish to return.

And it must be remembered that a lot of information about you will remain on the platform, from the posts of your friends.

One of the biggest changes of GDPR will be the right for people to be forgotten and, under these changes it should, in theory, be much easier to wipe your social network or other online history from existence.