With two months to go until the UK is due to leave the EU, how are firms and the UK economy faring?

The economy's "resilience through the turbulence of the Brexit process has been particularly noteworthy", according to Chancellor Philip Hammond.

But some businesses claim to have been put under unprecedented pressure.

What is going on?

It's impossible to put absolute numbers on how jobs, output and investment have been affected so far.

No one knows how these will have fared had the outcome to the referendum in 2016 been different.

Other factors have influenced the business environment - not least slower growth in the likes of China and Europe

But there is a range of evidence that can give us an idea of how UK companies are faring.

On the face of it: no.

The number of people employed is at an all-time high. But there's a lot going on under the surface.

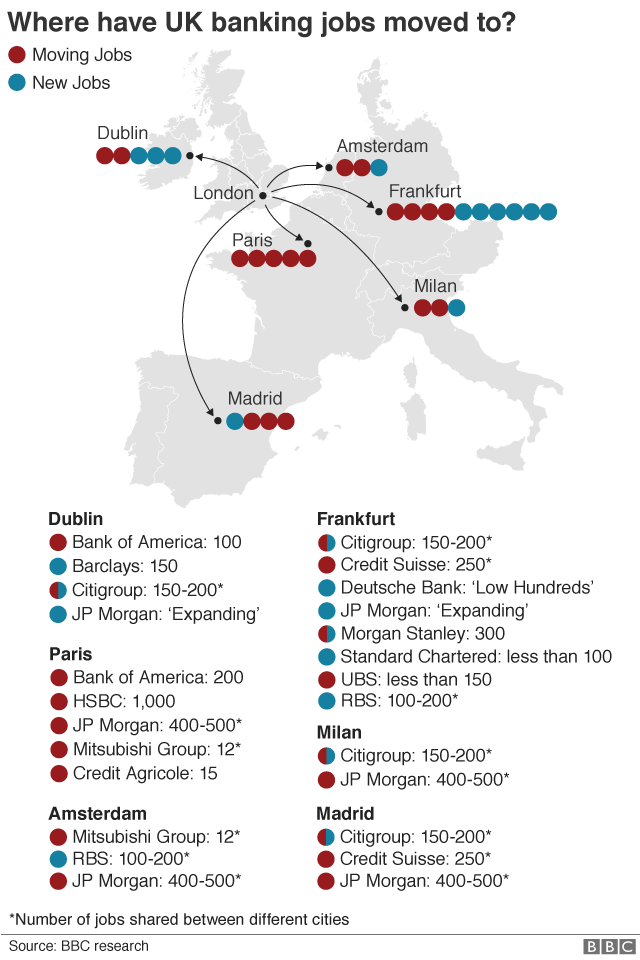

Banks' contingency plans mean setting up alternative bases in the likes of Frankfurt, Paris or Dublin. Individual banks are coy about revealing too much.

But reports about banks such as Morgan Stanley, Barclays and Bank of America moving, or creating, hundreds rather than thousands of jobs at those sites suggest the total affected in the City is much smaller than the 65,000 or so predicted by some immediately after the referendum.

London's Lord Mayor has said that the total by 29 March is likely to be below 13,000.

What we don't know is if jobs created in European cities such as Paris and Frankfurt are at the expense of potential ones here - or the final implications of the future trading relationship with the EU, whenever that is agreed.

While some - including JLR and Ford - have cited Brexit when cutting jobs, it has been a contributing rather than a deciding factor.

Car companies are facing a seismic shock in the face of slowing global demand, oversupply and the shift away from diesel.

In advance of departure, it is rare for firms to blame Brexit alone for job cuts. Chef and restaurant owner Jamie Oliver faced derision for doing so within a few months of the referendum, with critics instead blaming his business model.

As the uncertainty continues, companies may be putting hiring plans on hold - not least as they ramp up spending on no-deal contingency plans. How that impacts overall employment won't be known for a while.

There has probably never been a better time to be a trade negotiator - or a business adviser.

Overall employment has continued to rise to record levels since the referendum in June 2016.

In total, £95m worth of contracts were awarded last year to consultancy firms to advise the public sector on Brexit.

And 20,000 more civil servants have been employed since the referendum, in a reversal to earlier trends.

They are concentrated in the departments most affected by Brexit.

And that's just the public sector.

Some companies continue to hire apace for other reasons. Telecoms giant Openreach, for example, has said that it will hire a further 16,000 engineers to support its rollout of full fibre broadband.

Business investment is stagnant and more than 10% lower than official forecasts had predicted prior to the referendum.

A lifting of the uncertainty could persuade firms to start spending again - a "deal dividend".

But investment has been relatively sluggish since the financial crisis.

Firms instead opted to hang on to workers, as they are relatively cheap. They may be continuing this strategy, which could help explain why job creation has remained so resilient.

And as businesses enact contingency plans, money earmarked for investment may have been diverted.

Drugmaker AstraZeneca has spent £40m building extra testing facilities as it increases its drugs stockpile.

Some are forging ahead with plans for a variety of reasons.

Sony is moving its electronics HQ to the Netherlands, to pre-empt any customs problems.

James Dyson claims he's moving his company's base to Singapore to be closer to its fastest growing markets.

But luxury brand Chanel cited the same reason for moving its global business functions to London.

Majestic Wine has said it will stockpile more than one million extra bottles of wine from France, Spain and Italy

Drugmakers aren't the only ones stockpiling.

Associated British Foods, the company behind Twinings tea and Ryvita, has bought up extra machinery and packaging to prevent disruption to supply chains.

Mondelez, the makers of Cadburys, is stocking up on ingredients and the finished article.

With Majestic Wine buying an extra £8m in drinks, and Nestle investing in more coffee, there is a reduced risk of us having to forego some of life's luxuries.

Of course, these extra stocks may not be needed - and so the effort and money that's gone into organising and storing them will have been wasted.

But at this point, many companies feel they have no choice.

Fashion buyers are concerned about possible disruption

The UK's exit from the EU may be two months away but for some Brexit has in effect already happened.

Orders are often put in months in advance.

Those for British malting barley from the EU have dried up.

Barley, which is the UK's second largest arable export, could attract tariffs of around 50% of the current market price.

And it's not just food. At September's London Fashion Week, buyers were voicing concerns about placing orders for the spring that might face disruption.

Many of the impacts of the run-up to Brexit, as far as business is concerned, are likely to be temporary, reflecting contingencies or uncertainty.

The overall impact on the economy will become a bit clearer when GDP figures are released in about a week.

And what follows next will depend on Westminster's actions.

The impact of those, in whatever direction, may dwarf what we've seen so far.