In the eyes of the International Monetary Fund, a country that allows the value of its currency to be determined by supply and demand is demonstrating financial maturity. “Emerging market countries need to consider adopting more flexible exchange rate regimes as they develop economically and institutionally,” said a 2004 IMF paper whose lead author was the organization’s former chief economist, Kenneth Rogoff of Harvard. The IMF’s World Economic Outlook, released this month, says the commodity price bust has been harder on commodity exporters with pegged currencies than on ones with flexible exchange rates, which were able to shore up their economies without running up budget deficits or running down currency reserves.

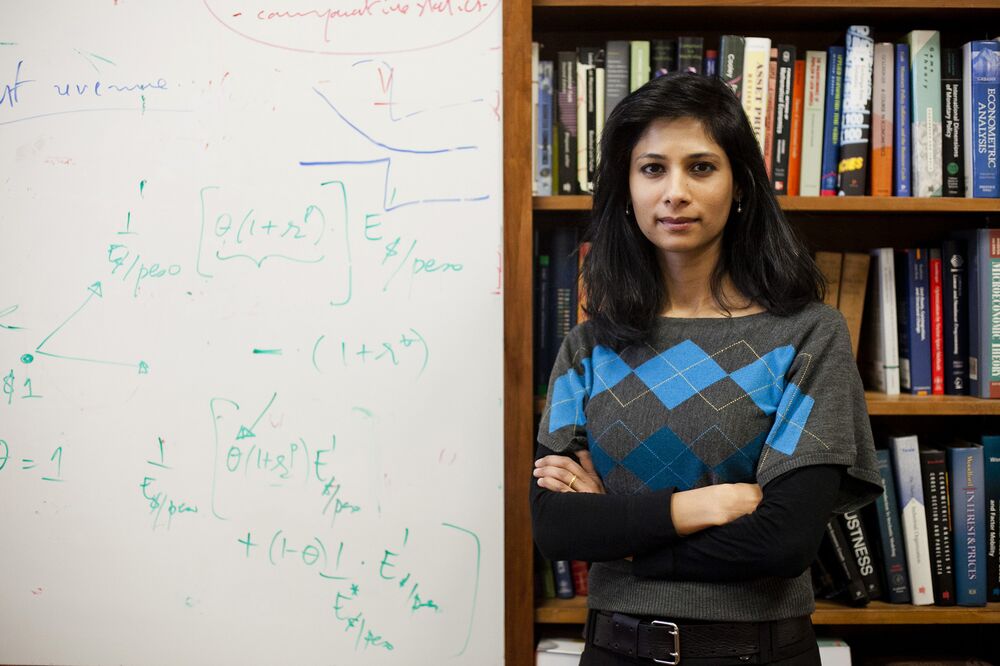

Yet a new paper by Harvard economist Gita Gopinath argues that some of the benefits of flexible exchange rates have been overstated. The conventional thinking is that a small country can boost growth by letting its currency depreciate because doing so makes its goods cheaper in world markets. But Gopinath cited new research showing that’s mostly not the case, at least in the short run, given that exports tend to be invoiced in dollars rather than the local currency. As a result, the argument for letting currencies float is “worse than you think,” Gopinath said in presenting her research at an Oct. 14 conference organized by the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

The fixed vs. floating debate goes back to the earliest days of the IMF, which was conceived in 1944 when the value of the dollar was still pegged to gold. The IMF’s advice has varied over the years as economic thinking has evolved. In 1953 the libertarian economist Milton Friedman invoked the concept of daylight saving time in a paper titled The Case for Flexible Exchange Rates. In theory, he wrote, everybody could decide individually to get up and go to bed an hour earlier in the summer, when the days are longer, but it’s more convenient to change the clock so everyone does it at once. Similarly, he wrote, if the prices of a country’s goods and services get out of line with those in the world market, “it is far simpler to allow one price to change, namely, the price of foreign exchange, than to rely upon changes in the multitude of prices that together constitute the internal price structure.”

The opposite solution is to surrender monetary independence. For example, Ecuador, Panama, and El Salvador have adopted the U.S. dollar; and Kosovo and Montenegro, the euro.

It’s the in-between countries—the ones that keep their own currencies but try to control their value—that face difficulties. A nation trying to defend an overvalued exchange rate can be overwhelmed by speculators who bet against it, as happened in 1992, when investor George Soros “broke” the Bank of England by forcing it to withdraw from the European Exchange Rate Mechanism, a precursor to the euro. Many economists have argued that currencies should be fully floating if they aren’t inalterably fixed. When Stanley Fischer was first deputy managing director of the IMF in 2001, he wrote that the trend away from softly pegged exchange rates “appears to be well established,” adding, “this is no bad thing.”

But Gopinath and other speakers at the Peterson Institute event emphasized that many countries remain in the murky middle—neither fully floating nor fully fixed—and that this is likely to persist. “The world is messy,” said Raghuram Rajan, an economist at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business, who was governor of the Reserve Bank of India from 2013 to 2016. India lets its currency float but sets a target for the inflation rate.

By the IMF’s reckoning, about 40 percent of its member nations have “soft pegs.” That’s an understatement because many countries that say they don’t have pegs in fact do, says Harvard’s Carmen Reinhart, who spoke at the Peterson conference and is co-author of a 2000 paper called Fear of Floating. Also, she points out, the IMF categorizes all members of the euro zone as floaters, even though they don’t float vs. one another.

Floating exchange rates can be lethal to small countries. When a currency appreciates, it can encourage inflows of hot money that create asset bubbles. Then, when investor sentiment changes, the sudden capital outflows can trigger a recession. That’s why few countries are willing to take a laissez-faire approach. Echoing Reinhart, Gopinath concluded: “Once you include all the other arguments for the disruptive effects of exchange rate flexibility in emerging markets, the rationale for ‘fear of floating’ is strengthened.”